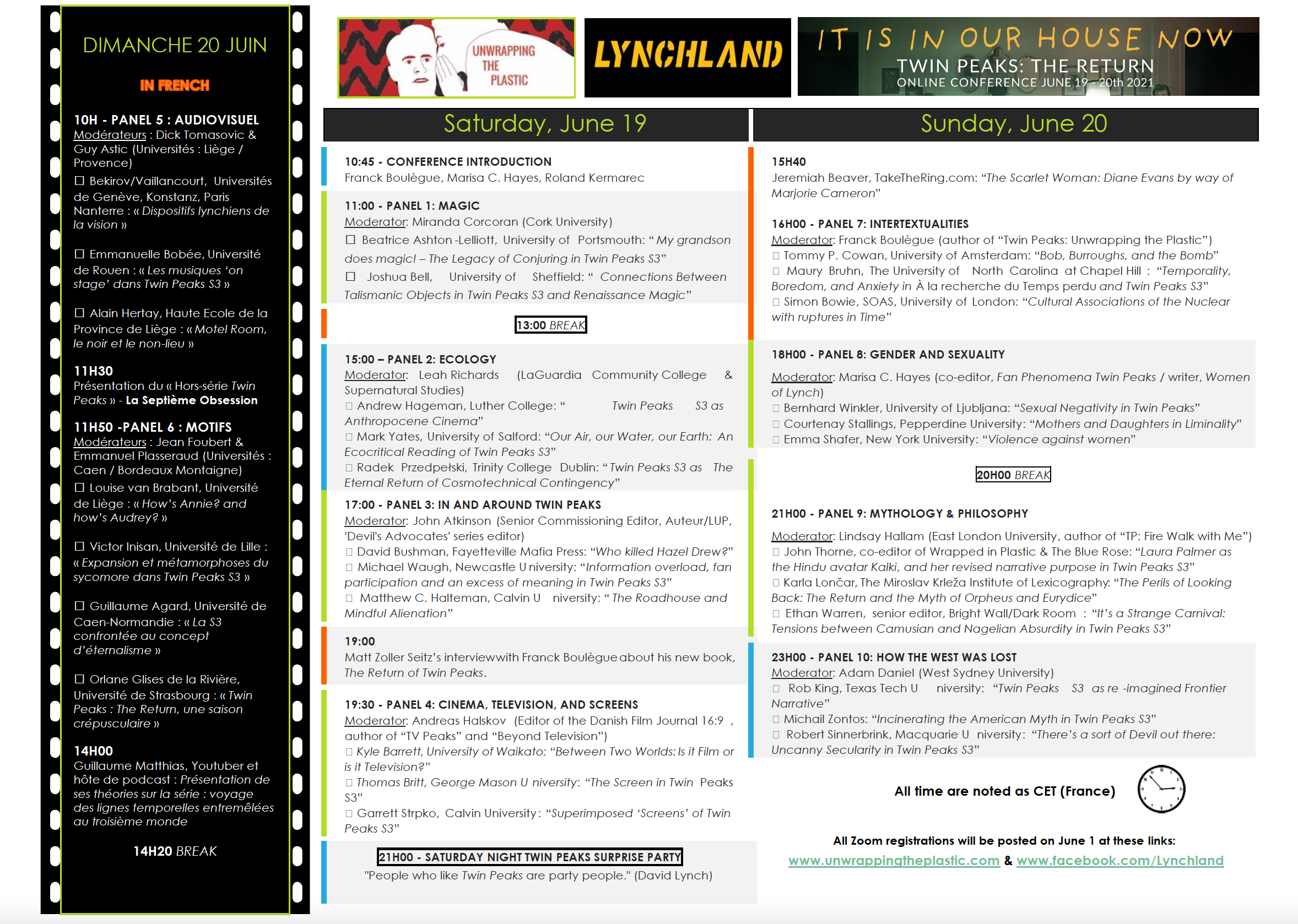

Finally!

It only took me something like 25 years or so, but I now believe I have a credible understanding of what the mysterious word “GARMONBOZIA” stands for. Of course, I’m aware of its meaning in the series and film (pain and sorrow) and of its appearance (creamed corn). But what I mean is the reason why it’s called Garmonbozia and not something else. Where does that word come from and how was it chosen?

I have suggested elsewhere that it might be linked to the Sanskrit language, knowing David Lynch’s interest in the Vedas. There is a certain musicality to the word that is reminiscent of the Indian diaspora. I also tried letter combinations, gematria, and multiple other methods of exploration and word play.

And then, I remembered that I had connected JUDY to Buenos Aires because of the letters one finds on a telephone dial. “J” stands for “5”, “U” for “8”, “D” for 3, and “Y” for 9″ – 58,39°W, the exact longitude of the Argentinian capital (“pure air”, from which the Lodge entities have descended).

What would happen if we apply the same method to the most cryptic word of all, “Garmonbozia” ? David Lynch’s interest in numerology and Mark Frost’s fascination for Ley lines are well established. So I looked on my telephone keypad and came up with the following series of figures: “42766626942”.

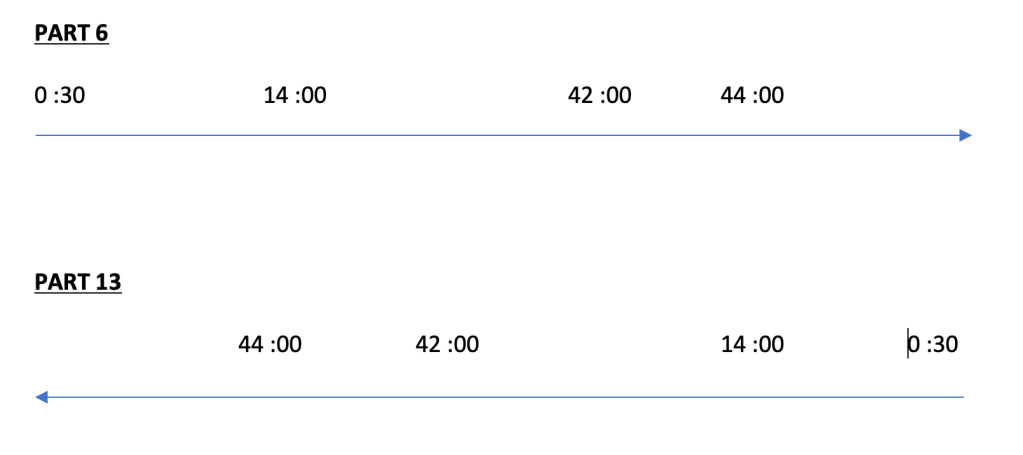

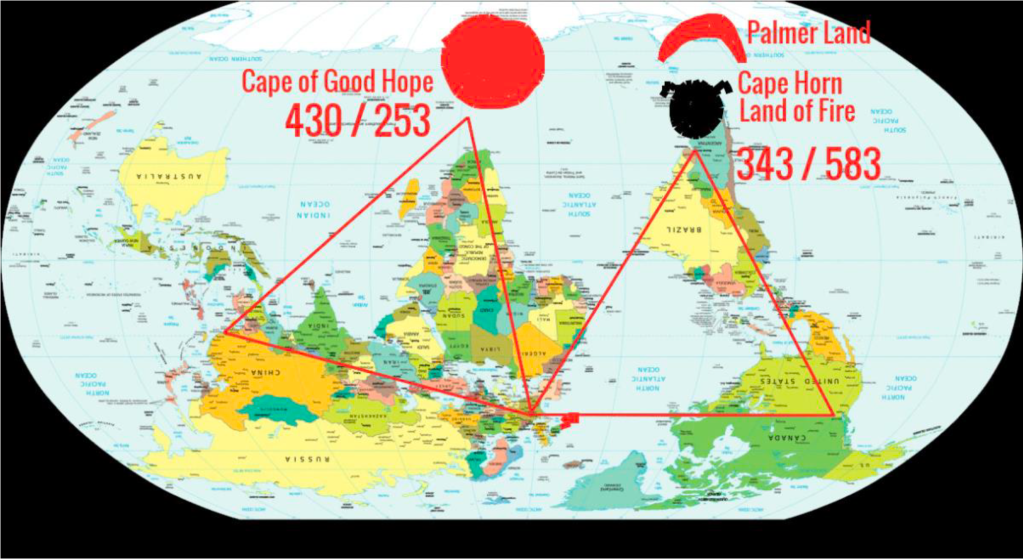

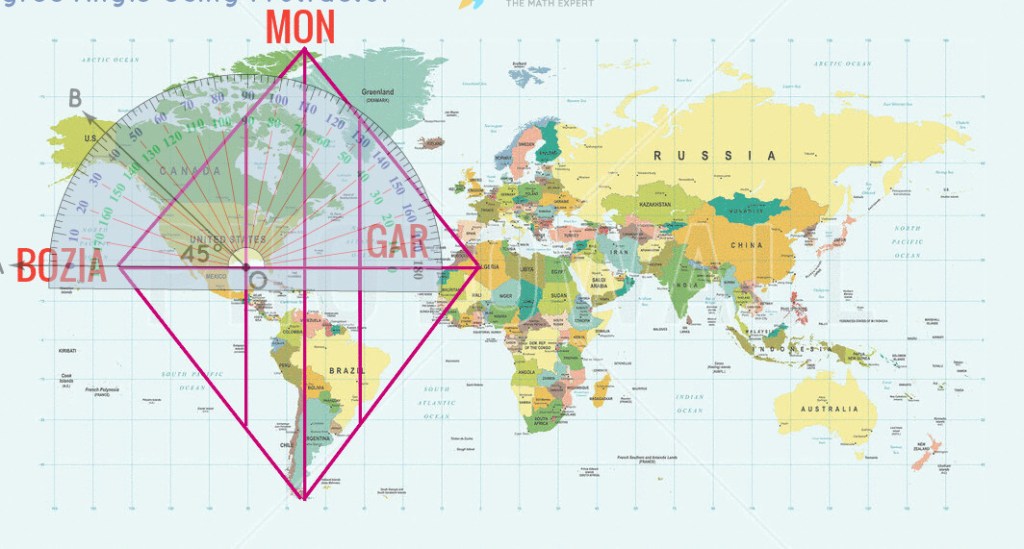

Based on the way the word is usually pronounced in Fire Walk with Me, I decided to split this number into three chunks/syllabes: “GAR/MON/BOZIA”, i.e. “427/666/26942”. This done, where was I supposed to look? Mirroring the process I had followed for JUDY and longitude, I turned the numbers into coordinates (42.7° / 66.6° / 26.942°) and looked for significant connections on a world map focused on the Americas, around which the series and film gravitate.

66.6° (666?) did not make much sense in terms of latitude, so I looked at the longitudes (East and West). Interestingly, the southernmost point of South America is exactly located at 66.6° West (south of the Tierra del Fuego / Land of Fire).

This by itself was a striking coincidence, but not enough to cry victory just yet. When I turned to North America, the numbers did not make sense: the northernmost point of the continent (if one excludes Greenland), is located above Canada at a latitude of 83° (but at the same longitude, 66.6°W).

What was the connection, then? Well, at this point, it was important to look at the latitude of the southernmost peak of the Americas: 56°. So, 83° in the northern hemisphere and 56° in the southern hemisphere – where was the middle point of that line on the 66.6°W longitude to be found?

At 83°N – 56°S = 27°N… i.e. at 26.942°N, the BOZIA in GARMONBOZIA!

I now had a line going from top to bottom of the American continents, split in its middle at 27°N by a point apparently devoid of meaning, somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean.

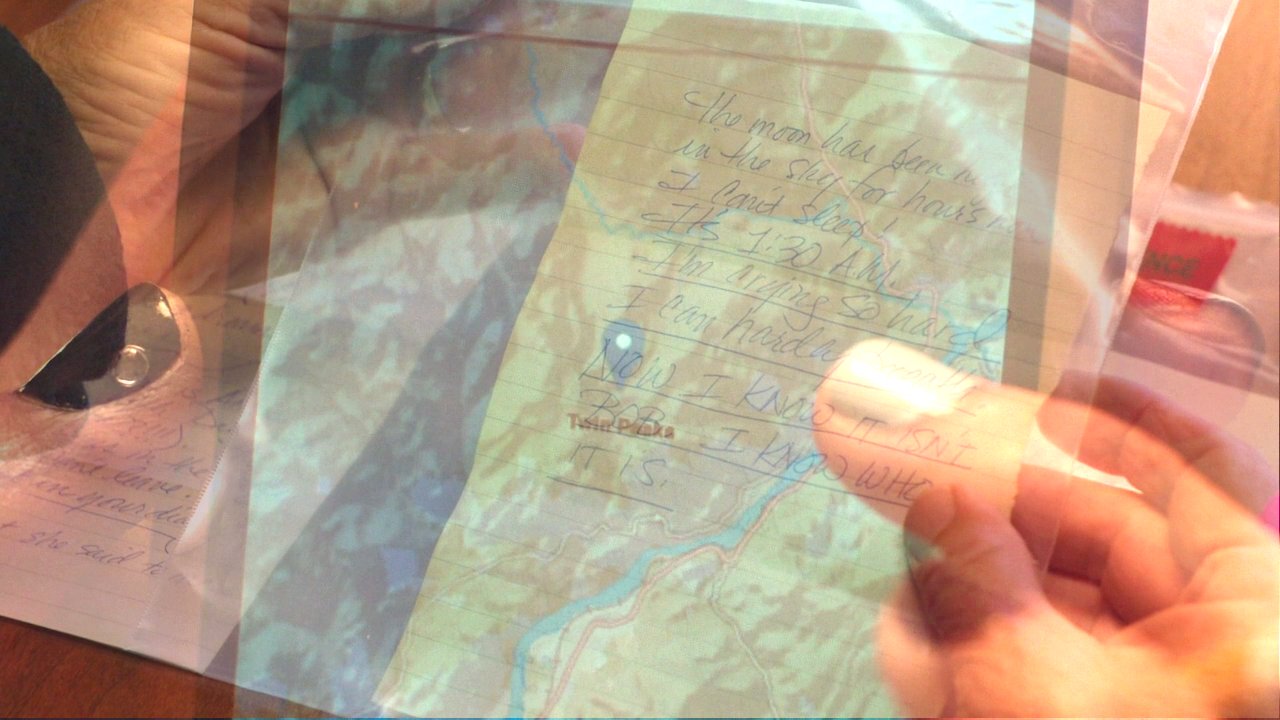

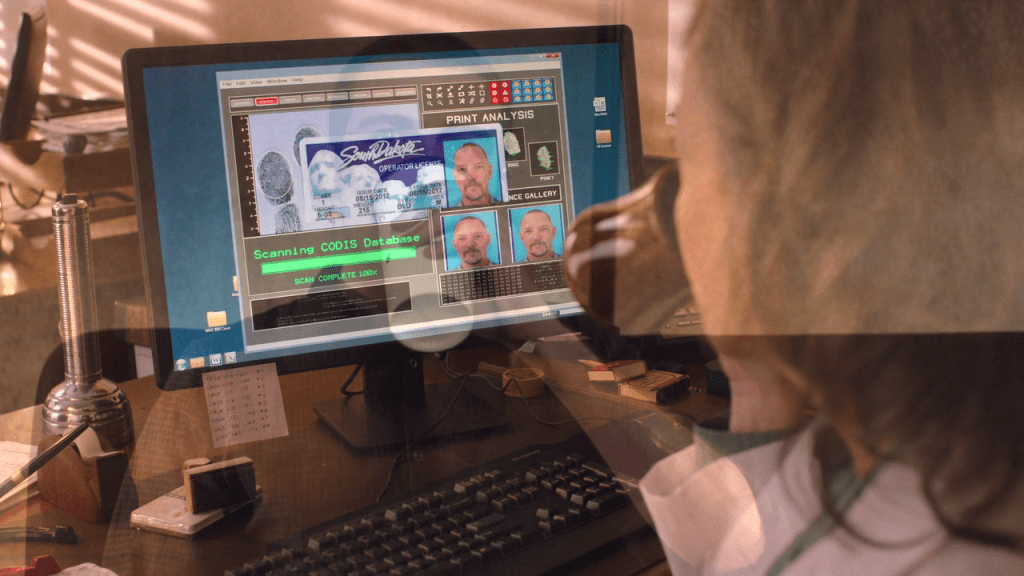

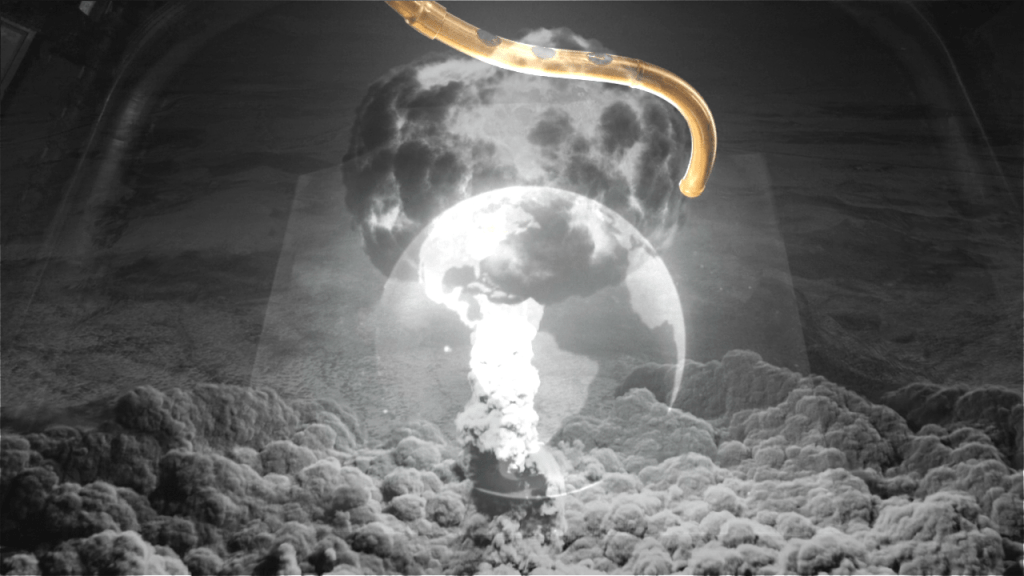

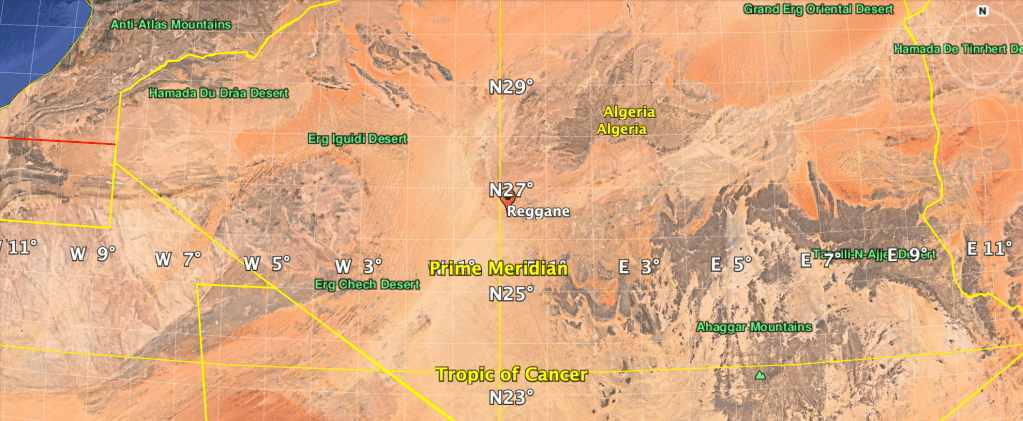

This led me to draw a perpendicular line to the MON/666. I had already looked for significant points within the context of the show: too high for Hong Kong, too low for Tibet or the USA… The only thing I could think of was the Sahara desert, mentioned in part 3 of the return (Jade’s car), but the line was too low for most places of interest in Egypt, for instance. Then, being French, I suddenly remembered that France has conducted various civilian and military ballistic rockets launches from the vicinity of the town of Reggane until 1965, and had also conducted four nuclear tests there during the Algerian War in 1960 and 1961, before the country’s independence. Given the importance of nuclear bombs in Twin Peaks (see part 8), it was worth looking at the town’s latitude. As evident on the image below, Reggane is located at 27°N, the one bisecting the North / South axis of the Americas at 66.6°W.

Beyond the French nuclear tests, I believe this choice also leads to the works of authors such as William Burroughs and Brion Gysin, who wrote abundantly about the Sahara and its spirit, Ghoul. Links between the desert and evil entities are clear in part 8, and it is no surprise that a Sumerian demon such as an utukku (Judy) would be attracted to such a hostile location.

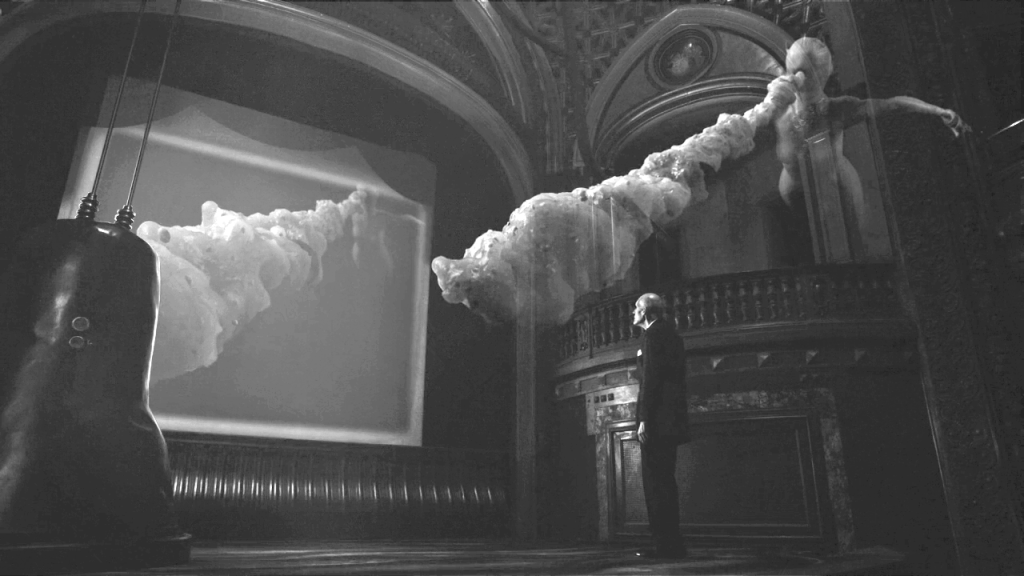

I now had four points on my map, which I completed with a fifth somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, on the line running from Reggane to the middle of the 66.6°W line, at a similar distance West from the line in question as Reggane is located to its East. Joining the various points, a huge parallelogram was now engulfing most of the American continents and a small portion of West Africa. Interestingly, this parallelogram was highly reminiscent of the motif of the owl cave / owl ring.

It also seems that, taking the point where the North/South and East/West lines meet, the direction of Twin Peaks lies approximately at an angle of… 27°! It would be interesting to measure this more precisely, but this number does indicate the general direction of the Northwest Pacific town…

After the MON and BOZIA elements of the words, remained the question of the GAR (42.7°). I remembered that Rio de Janeiro was located at 43.0° West (Remember: 430), and decided to look what a North/South line at these coordinates would look like. I added a second parallel line to the West of the North/South divide, located at 42.7° East of the westernmost point of the East/West line, i.e. at 90.4° West. So two new lines: one at 42.7°W and the other at 90.4°W (i.e. roughly by the Mississippi delta).

The interesting thing here is that when one traces a straight line from the point where the line between the Tierra del Fuego and Reggane meet the 42.7°W longitude, and extends it through the point where the 90.4°W line meets the East/West axis, the line drawn ends up pointing at Twin Peaks too. The map below needs some improvements, but it makes my point nonetheless clear. By adding the two 42.7° vertical lines to the parallelogram, it becomes possible to find out where Twin Peaks is located.

It is also possible to reach the same conclusion by drawing a line starting from the point where the 90.4°W line meets the East/West axis at an angle of 42.7° (GAR), as made apparent below:

GAR, MON, and BOZIA therefore are not first and foremost to be understood as carrying a linguistic meaning – they are coordinates on a treasure map.

And the gold is buried in Twin Peaks!