Although my abstract was selected by the conference committee for the upcoming James Joyce Symposium at Trinity College in Dublin, I am sad to announce that for various personal and professional reasons, I will not be able to travel to Ireland this June to give my presentation about the links I have found between Twin Peaks: The Return and Ulysses. Nonetheless, in an attempt to trace the research I had prepared for the conference, I have decided to share my notes in the form of a blog post. These thoughts include previously-published ideas found in my book The Return of Twin Peaks, alongside additional insights, both textual and visual, regarding what, in my opinion, links the two works.

First, I believe it is important to establish why reading Twin Peaks through the lens of Ulysses (and vice versa) makes sense:

- To start with, Mark Frost has mentioned on several occasions the role that Homer’s Odyssey played in the development of the script: “- Did Homer’s Odyssey play any role in the conception and construct of season three? – I did have The Odyssey in mind, but Lynch was not overly familiar with it, so I kept that to myself.” (David Bushman & Mark Frost, Conversations With Mark Frost). The Return, just like Ulysses, recalls and recasts events from The Odyssey.

- It is worth noting — although it remains anecdotal and does not confirm that Ulysses played a role in season 3 — that Frost spent time in Ireland while he was working on Goddess, the project that somehow led to Twin Peaks. Even though this is very indirect evidence, it should nonetheless be mentioned due to the celebrated role that Joyce holds in Ireland and the ways in which Ulysses has permeated contemporary Irish culture.

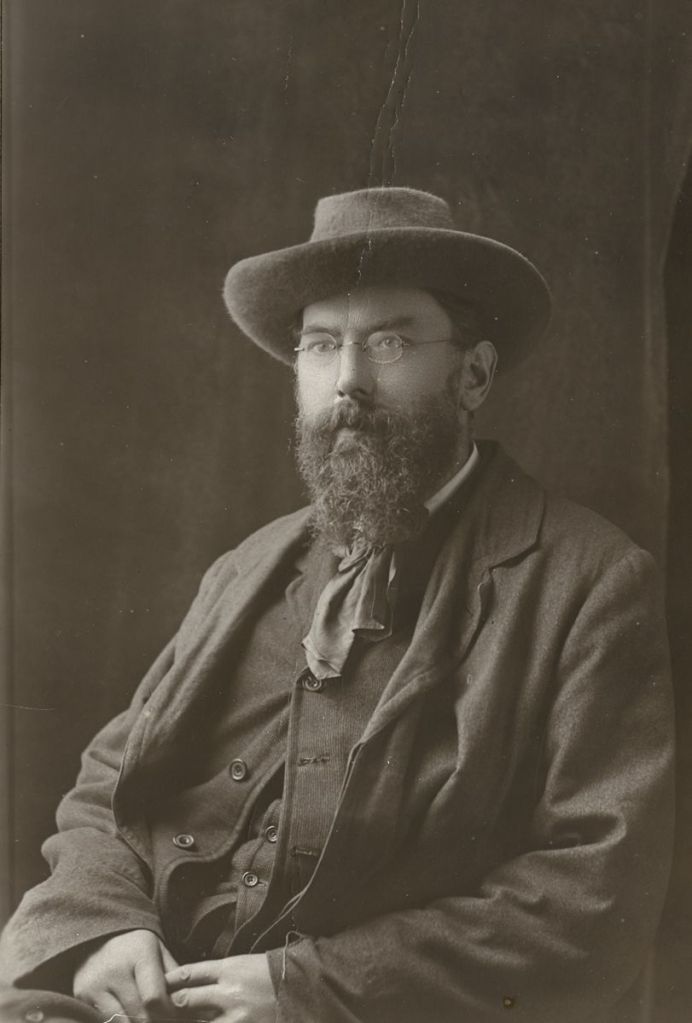

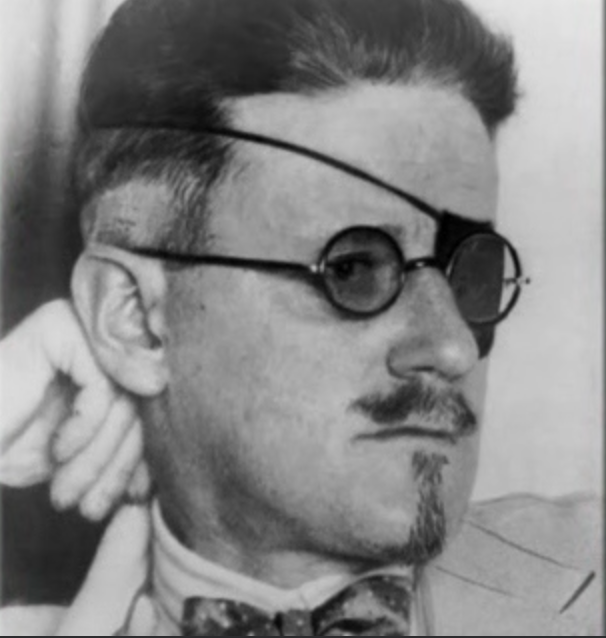

- We also know that Lynch reads Joyce: “With James Joyce, word combinations conjure things. He uses them as an art form and a language for abstractions. Cinema is its own language. As the sound and picture get going and things begin to happen, it can get pretty abstract, but it’s a language that says something that can’t be said in words — or maybe could, by a poet“. Additionally, Frost is clearly a well-read author, as evidenced in Bushman’s Conversations With Mark Frost, in which he copiously quotes from a wide variety of works from world literature and world cinema.

- Alongside Ulysses, I argued in a former blog post that Finnegans Wake was also referenced in season 3. Since Ulysses and Finnegans Wake are considered twin works (the book of the day and the book of the night), It makes sense that if one figures in The Return, the other would as well.

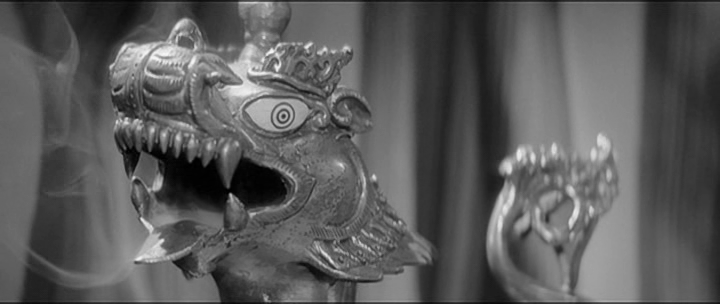

- As one reads Ulysses, it becomes apparent that the work (is it really a novel?) shares with Twin Peaks a common interest in Theosophy, Helena Blavatsky’s spiritual tradition. Blavatsky, the Akasic records, and planes of consciousness, are mentioned at several instances during the course of Joyce’s Ulysses. Set in 1904, the narrative of Ulysses runs concomitant to the spiritual movement’s heyday. Also, being set in Dublin, one cannot escape the fact that several of the best known writers of the day were theosophists themselves, including William Butler Yeats and George William Russell (who wrote with the pseudonym Æ ).

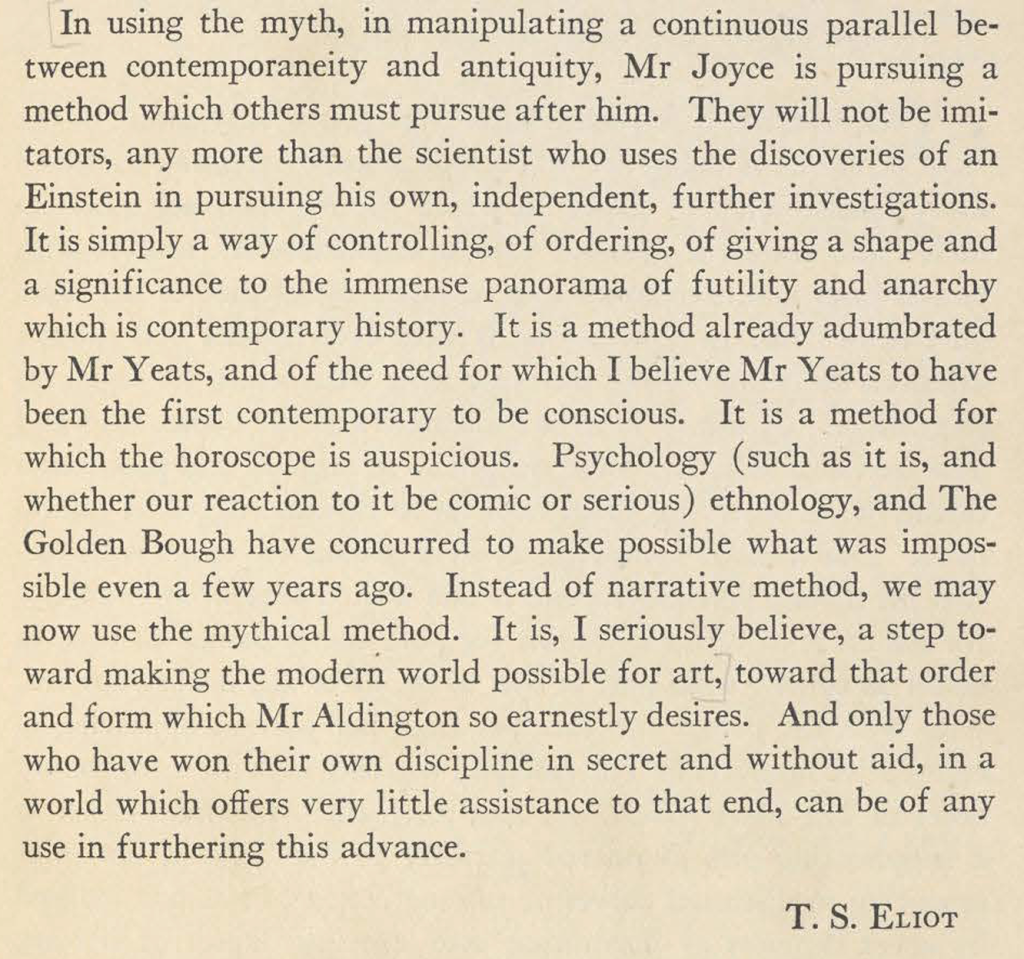

- Like Ulysses, the action of Twin Peaks takes place at the confluence of two orders of literary time: dramatic time and epic time. If Ulysses depicts the drama of a single day (Bloom’s Day: 16th June, 1904), it also paints the whole course of a major phase in the life of its characters. Both works, as every epic, begin in media res, but that’s also where they remain (in the present tense). The Return does not take place over just one day — but one could be argued that it nevertheless does, in a figurative sense : not a full rotation of the Earth on its axis, but a cosmic/Brahma day (“Someone was to read them there after a few thousand years, a mahamanvantara” — a Day of Brahma is 4,320 million years) — the first part of season 3 opens at dawn with Doctor Jacoby, and the last segment of part 18 closes in front of the Palmer house in the middle of the night. Cooper’s Brahma Day takes place in 2016, 102 years after Bloom’s Day. Similarly, the journey of The Odyssey takes place over a period of 10 years. The time of heroes in myths and the time of humans in reality do not flow at the same pace. TS Eliot actually once argued that Joyce made the novel obsolete by replacing the narrative method (consistency in the point of view) with the mythical method (parallels between contemporaneity and antiquity). Ulysses and The Return are ancient and modern all at once, Bloom and Cooper being reincarnations of Homer’s hero.

- Another point worth noting is that both Ulysses and The Return take place at moments of crisis: the action of Ulysses develops during the debate over the land reform and Home Rule in Ireland. Similarly, season 3 depicts the effects of the 2008 financial crisis, and even though it was shot before Donald Trump was elected, one can nonetheless feel the populist impact of the politician and his voters within its narrative.

- Perhaps most importantly, both The Return and Ulysses are composed of 18 parts/chapters. This is a slightly atypical number of episodes for a television season. Indeed, since the late 1960s, the broadcast programming schedule typically includes between 20 and 26 episodes. Why 18 parts, then? Besides Frost’s love for golf (18 holes), the link with Ulysses appears like a sound bet. While the connections with The Odyssey are undeniable, one needs to remember that the epic poem is composed of 24 books, not 18. The link that can be drawn between The Return and Ulysses is of a structural order, much more so than owing to the various characters and elements they contain (which can also be connected to The Odyssey).

- A series of other themes creates bridges between the third season and the novel: metempsychosis and reincarnation (think of the many incarnations of Laura Palmer, for instance); free-masonry (Leopold Bloom belongs to a Lodge and the free-masons play an important role in Frost’s The Secret History of Twin Peaks); questions of motherhood (Stephen’s mother in Ulysses is of the utmost importance, just as Sarah comes to mind in Twin Peaks); homelessness and homecoming (Stephen ends up homeless in Ulysses while Leopold returns to his home; the Woodsmen are described as homeless people in The Return and Laura is the homecoming queen).

Because of the palimpsestic nature of season 3 (a palimpsest is a manuscript, typically of papyrus or parchment, that has been written on more than once, with the earlier writing incompletely scraped off or erased that remains partially legible beneath the new layer of text –> The Return is rewriting Ulysses which is retelling The Odyssey, and with each of them, one can still find visible traces of the original model), intertextuality is at the core of the story. While telling their tale, Lynch and Frost are also retelling various other tales, both literary and filmic, connected to the surface narrative by a myriad of references. Of course, this paper focuses on the links with Ulysses, but it is important to note here that this is only one level of intertextuality. Others have already been discussed on this blog in the past (The Wizard of Oz, for instance) and I am currently preparing another post about the links I have recently found with another return/nostos story: The Count of Monte-Cristo. Coming soon!

Another thing that needs to be said before I dive into specific episodes and what unites Ulysses and The Return is the fact that beyond Cooper’s and Laura’s odysseys, Stephen’s and Bloom’s, the season and the novel include a variety of characters who follow their own “minor” odysseys in both works. I have not yet spent enough time analyzing each and every one of these examples, but they certainly contribute to the richness of both worlds.

As mentioned above, the season is composed of 18 parts. My argument is that each part of The Return reflects what takes place in the corresponding chapter of Ulysses. Moreover, the general outline of the narrative follows that of the book:

- a 3 parts-long moment akin to The Telemachiad,

- followed by 12 parts mirroring The Wanderings of Ulysses,

- concluding with a segment of 3 parts echoing the final Homecoming (the nostos, the return).

THE TELEMACHIAD

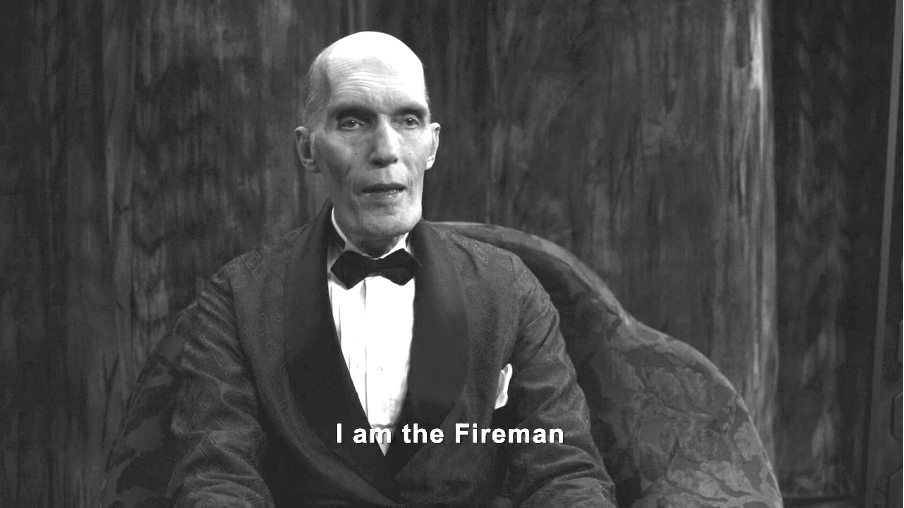

1- Telemachus

Before we begin with Ulysses as such, let’s note first that The Odyssey opens with a council of the Gods during which Zeus decides it is time for Odysseus to return home. It is fitting then to consider the opening dialogue between The Fireman and Cooper, before the action of The Return truly starts, as akin to this council. Cooper and his doubles (Mr. C, Dougie Cooper, Richard) are the equivalents of Odysseus/Ulysses during the course of season 3. Not only that: they are also impersonating Telemachus, Ulysses’ son, as the parting words between The Fireman and Cooper tend to prove: “you are far away”, he says, before Cooper disappears/disintegrates/teleports. It so happens that Telemachus’s name in Greek means “far from battle”, or perhaps “fighting from afar”, as a bowman does – far, in space or time.

The first three chapters of Ulysses (The Telemachiad) follow Stephen Dedalus (Telemachus) before we turn to the character of Leopold Bloom (Odysseus) with the next 12 chapters. The same outline is used in The Return, Cooper’s actions first echoing those of Dedalus/Telemachus until part 4 (the end of part 3, really), when he becomes more like Odysseus than his son. Indeed, one could argue that Cooper represents both father and son in The Return — the original Cooper being copied, doubled, cloned, by Mr. C, Dougie Jones, his “children” of sorts.

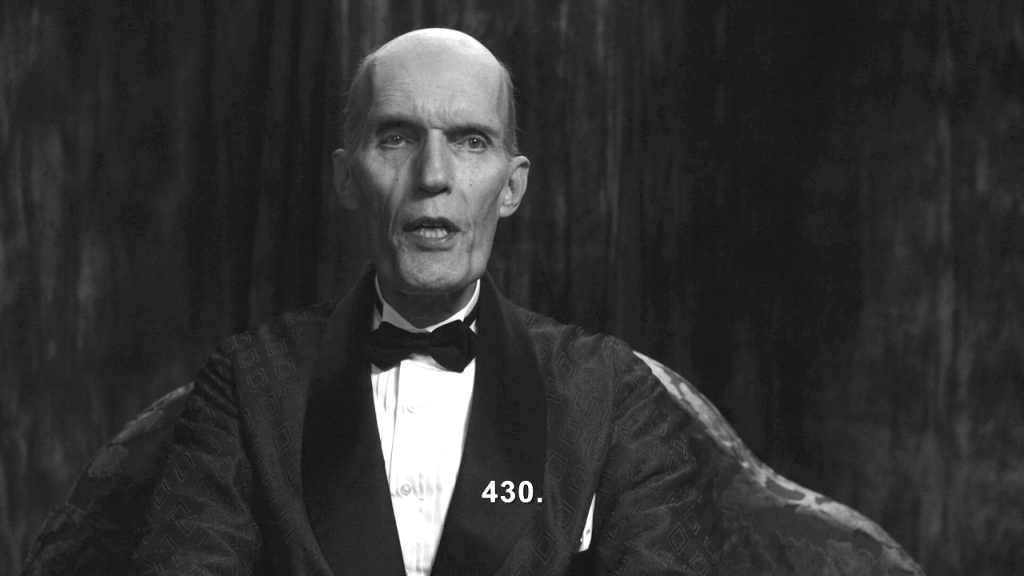

Ulysses revolves around the affair Bloom’s wife Molly is having with a certain Blaze Boylan, the manager of her upcoming concert in Belfast, while Leopold is wandering around Dublin on this special day at the beginning of the 20th Century (Joyce chose the day he began his relationship with Nora Barnacle, his wife-to-be, for Bloomsday — which becomes something of a Doomsday in The Return). While on the beach, in chapter 13, for a brief moment of respite between various vexations, he notices that his watch has stopped at the exact time when Molly and Blaze have consummated their affair: 4:30.

As the Fireman would say: remember 430.

The central theme of Ulysses chapter 1 is that of usurpation. The novel takes place in a country, Ireland, that has been stolen by an invader, the United-Kingdom, which imposed its own language (English) at the expanse of the island’s native language, Gaelic, almost extinct in 1904. Similarly, Mr. C has usurped Cooper’s life, led his life by procuration, pretending the former’s life belongs to him. This is also what the various thought-forms/tulpas of the season do.

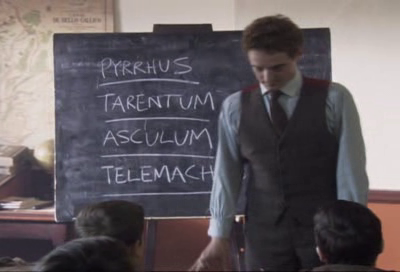

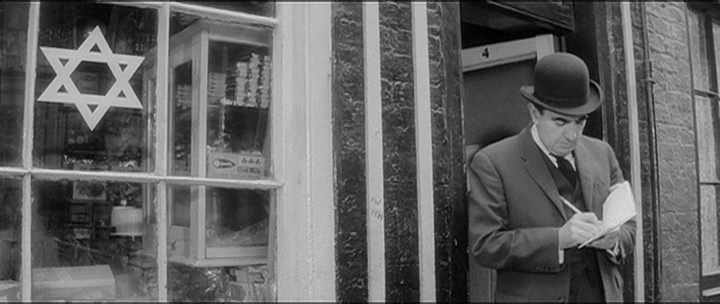

2- Nestor

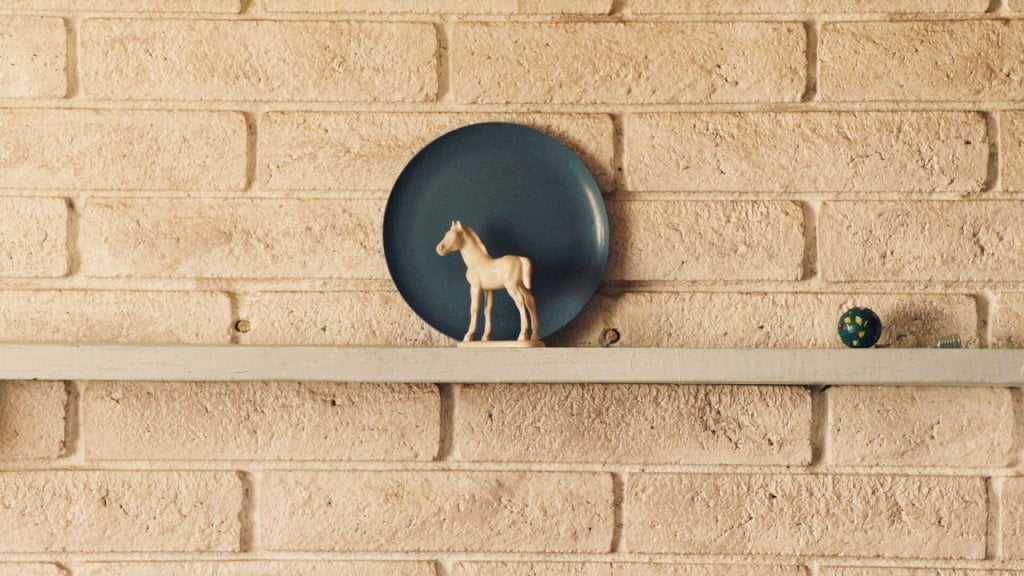

In Ulysses chapter 2, the young Stephen Dedalus (Joyce’s alter ego) gives lessons in a south-Dublin school to earn money and is handed a manuscript by his boss Deasy, who asks him to try and get it published in one of the town’s newspapers. It is a letter concerning a possible solution he has come up with for the foot and mouth disease currently plaguing the country. Deasy is the opposite of Nestor, the wise and respectable old man, king of Pylos, whom Telemachus goes to see when hoping to get information concerning his father’s whereabouts. Deasy is sententious, arrogant, and racist (strongly antisemitic). But like Nestor (the master charioteer), he has a strong interest in horses: “Framed around the walls images of vanished horses stood in homage”.

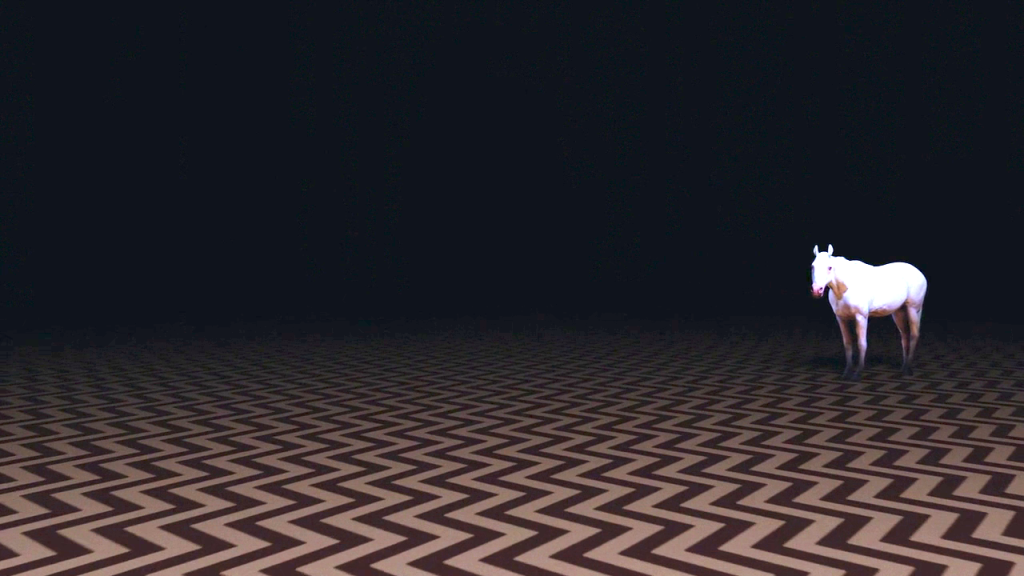

The character in The Return whose role is closest to Nestor is likely MIKE. He behaves as Cooper/Telemachus’s mentor, in part 2 and during the rest of the season. It is also in his realm of the Lodges that we first see the white horse associated with Laura, reminiscent of Nestor’s role as a charioteer and of Deasy’s interest in races.

Concerning Deasy’s antisemitism, one might wonder if the various sequences with intermodal containers carried by trains that intercut the season might not be a hint of the fate of the Jewish people during World War II. The links to WWII are clearly established in part 8 with the Trinity Test explosion, and the name of the main evil force in The Return — Judy — is reminiscent of Judaism. The indirect parallel Deasy makes between the foot and mouth disease and the Jewish people, whom he blames for “England’s decay” echoes here. One needs to remember that in 1904, three-fourths of the land under cultivation in Ireland was devoted to cattle and crops as a result of England’s policy to suppress industry on the island. As the Jews were literally the king’s chattel, one wonders if the situation in Rancho Rosa is not somehow meant to reflect all this. Stephen Dedalus might be right when he says: “History… is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake”.

So does Cooper.

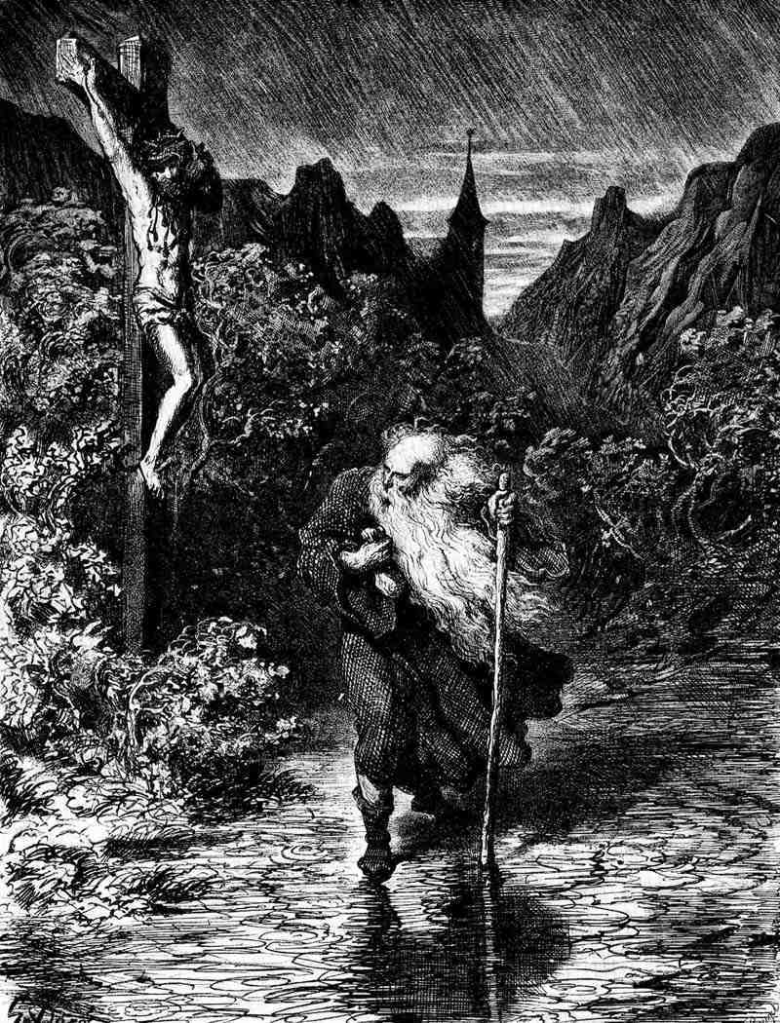

What is certain, though, is that Cooper represents another mythical figure of the returner in relationship to the Jewish people: that of the Wandering Jew (a legendary Jew who taunted Jesus on the way to the Crucifixion and who was cursed to walk the Earth until the Second Coming as a punishment). This is important because Leopold Bloom, Stephen’s surrogate father, is of Jewish origins and regularly experiences antisemitic acts and insults during the course of the novel – and as Cooper is both Ulysses and Telemachus, he is also both Bloom and Dedalus. “They sinned against the Light, Mr Deasy said gravely. And you can see the darkness in their eyes. And that is why they are wanderers on the earth to this day”.

Cooper’s wanderings start when the floor of the Lodges opens up under his feet and he plunges into outer-space. This is another moment that echoes chapter 2 of Ulysses: “For Lycidas, your sorrow, is not dead, Sunk though he be beneath the watery floor” (Milton). Him that walked the waves : Cooper is both a Jesus figure and the Wandering Jew.

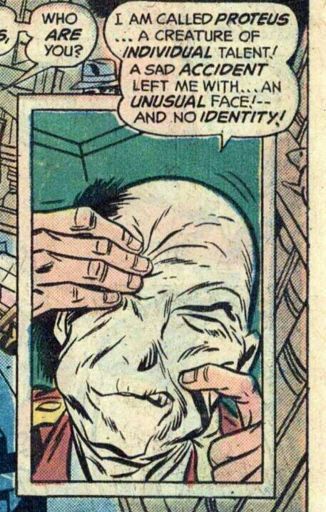

3- Proteus

Ulysses‘ third chapter is famous for its stream of consciousness interior monologue (which owes a lot to Edouard Dujardin’s 1887 novel Les lauriers sont coupés (The laurels are cut) — except that in The Return it’s a specific type of laurel, i.e. Laura, that got cut), accompanying Stephen’s meditative walk along the beach. Most of the chapter takes place inside his head. One could argue that it is as experimental and abstract as episode 3 of The Return, part of which also takes place by the sea (“our mighty mother”, primal matter), in Naido’s realm.

The chapter actually begins with the following words: “Ineluctable modality of the visible… Shut your eyes and see”. Difficult no to think of Naido in relationship with such a statement.

Since Stephen Dedalus is at the heart of the chapter, it is important to remember that in Greek mythology Icarus was the son of Daedalus, creator of the wooden cow for Pasiphaë, the Labyrinth for King Minos of Crete which imprisoned the Minotaur, and wings that he and his son Icarus used to escape Crete. It was during this escape that Icarus did not heed his father’s warnings and flew too close to the sun; the wax holding his wings together melted and Icarus fell to his death. With Cooper being Stephen’s alter ego in The Return, his cosmic fall in part 3 should come as no surprise.

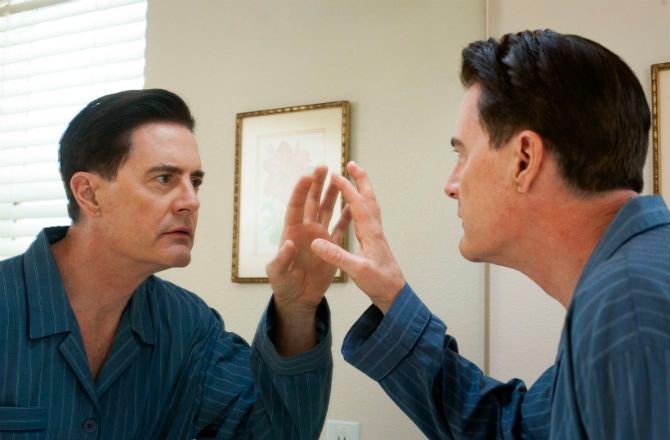

The chapter is named after Proteus, an early prophetic god of rivers and oceanic bodies of water. Able to foretell the future, he would change his shape to avoid doing so and answer only to those capable of capturing him. From this feature of Proteus comes the adjective “protean”, meaning “versatile”, “mutable”, or “capable of assuming many forms”, like the water in the ocean. Besides the fact that this is referenced in part 3 by the presence of the purple ocean, one also might reflect on Cooper himself, who undergoes a process of mutation when he is transported from Naido’s realm to Rancho Rosa via an electric outlet. Not only does his body become fluid, stretches in improbable ways, but his very personality mutates too from point A to point B. He becomes Dougie Cooper, an immature version of himself. He is “reborn”, as the whole chapter equates the sea to a mother, and Naido’s place is highly reminiscent of a womb.

Just like Proteus, Dougie Cooper seems to be gifted with the power of prophecy when he goes into the Silver Mustang Casino. He appears to know which slot machines are about to win a jackpot and uses this ability to amass a large sum of money.

It is also worth noting that Ulysses chapter 3 corresponds to Telemachus’s visit to Menelaus, king of Sparta, and his wife Helen in The Odyssey. The rape of Helen by Paris is at the root of the Trojan war. But in Ulysses, one finds a slightly different story: “Another version of the Helen of Troy Story… only an ‘imitation’ of Helen went to Troy with Paris, while the real Helen… sat out the Trojan War under the protection of King Proteus of Egypt”. Could Naido be this ‘imitation’ of Helen, while the real Diane remained trapped in the Lodges?

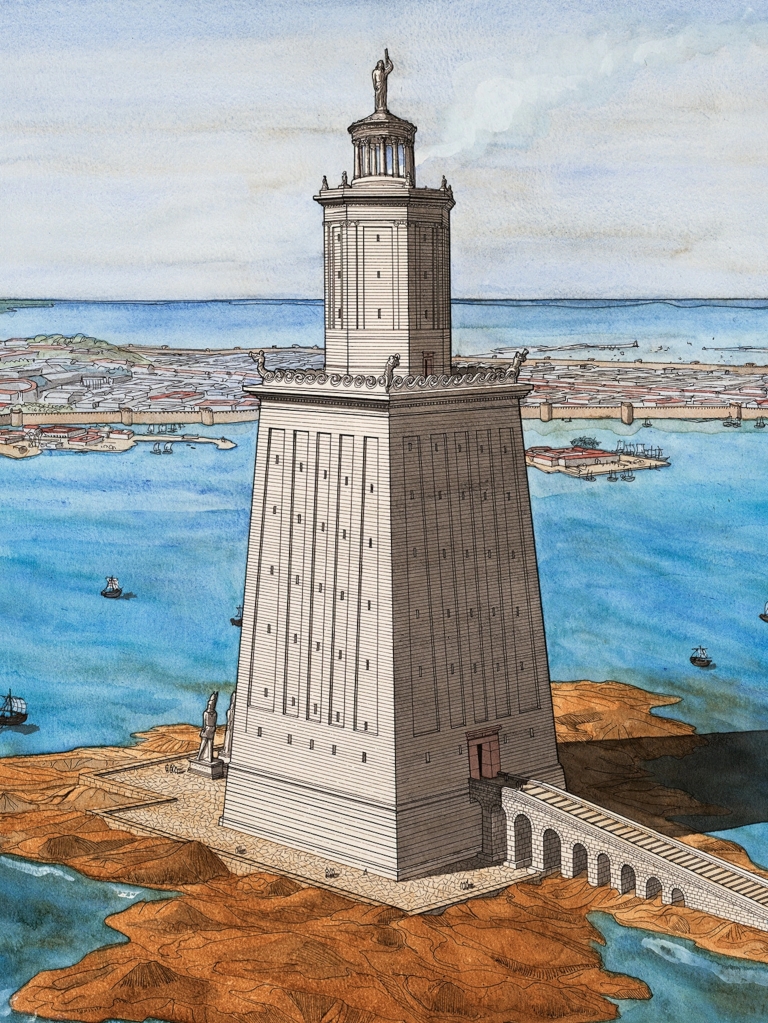

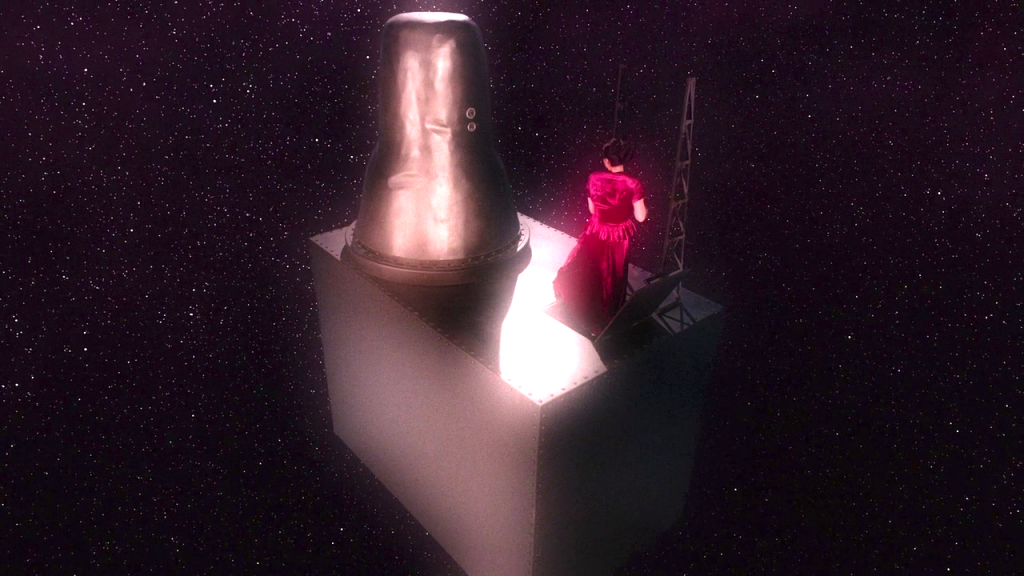

Interestingly, Proteus was associated with the island of Pharos, his residence in Homer’s Odyssey. It is on this island that the Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was built. Is Naido/Diane kept prisoner inside the equivalent of that lighthouse, the electrical device on-top of the structure being akin to the lamp of the building?

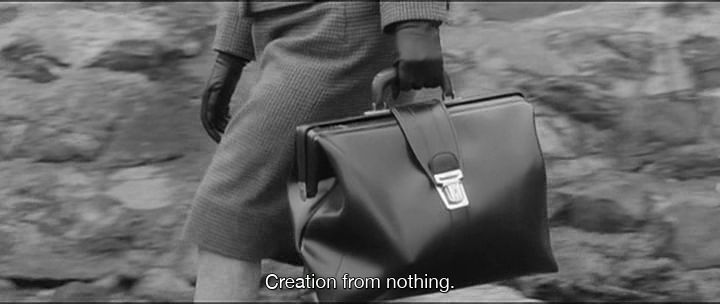

Additionally in this chapter, note the references to birthing which can be found on several occasions: “coming down to our mighty mother… her midwife’s bag… One of her sisterhood lugged me squealing into life. Creation from nothing”. There is no denying that Cooper’s arrival in Rancho Rosa is both a transformation and a sort of rebirth, also linked to Egypt with the visual reference to Osiris and the fact that Jade drives a “Sahara” car.

THE WANDERINGS OF ULYSSES

4- Calypso

After having focused on Stephen Dedalus during its first three chapters, Ulysses then moves on to his father figure, Leopold Bloom, the “hero” of the book. Similarly, part 4 is the first segment of the season completely dedicated to the wanderings of Dougie Cooper, the new version of our protean FBI agent.

In both works, the narrative does not necessarily progress in a linear temporal fashion, but in a spatial one, in which sequences are juxtaposed next to each other. The story is always on the move and evolves according to the principle of the synchronised narration, of the “meanwhile” narration – telling two or more stories that take place at the same time (events in Las Vegas, Twin Peaks, Buckhorn, sometimes simultaneously).

While Bloom sells advertising space for a living, Dougie works for an insurance company. Bloom’s house is in the northwest quadrant of Dublin, and Cooper’s spiritual home is of course Twin Peaks, in the northwest of the USA. And just like Leopold is “the people’s prince”, Cooper is Laura’s knight. While Bloom is truly Odysseus’ reincarnation, so is Cooper. The question of reincarnation actually plays a central role in chapter 4, when Bloom explains the meaning of the word “metempsychosis”, the “return” of the soul, to his wife Molly, his Penelope: “Metempsychosis, he said, frowning. It’s Greek: from the Greek. That means the transmigration of souls… Reincarnation: that’s the word. Some people believe, he said, that we go on living in another body after death, that we lived before. They call it reincarnation. That we all lived before on earth thousands of years ago or some other planet. They say we have forgotten it. Some say they remember their past lives… Metempsychosis, he said, is what the ancient Greeks called it. They used to believe you could be changed into an animal or a tree, for instance. What they called nymphs, for example”.

Cooper’s 25 years-long sojourn in the Lodges was akin to death, and now he is reincarnated as Dougie, a new avatar. Like Bloom, he is not conscious at the beginning of the season that he is the reincarnation of a hero (an FBI agent of ulyssean proportions). Little by little, though, he will start remembering snippets of his past life.

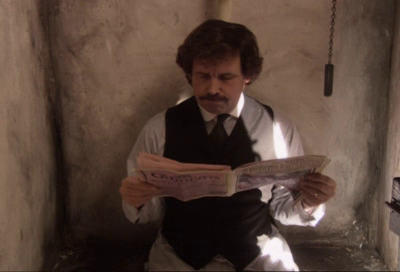

Bloom, like Dougie Cooper, cherishes the needs of the body. They both love to eat, for instance. And they both enjoy bodily functions a lot: while Bloom happily defecates in chapter 4 (“Quietly he read, restraining himself, the first column and, yielding but resisting, began the second. Midway, his last resistance yielding, he allowed his bowels to ease themselves quietly as he read, reading still patiently, that slight constipation of yesterday gone… feeling his water flow quietly”), Dougie is seen taking intense pleasure from peeing in part 4.

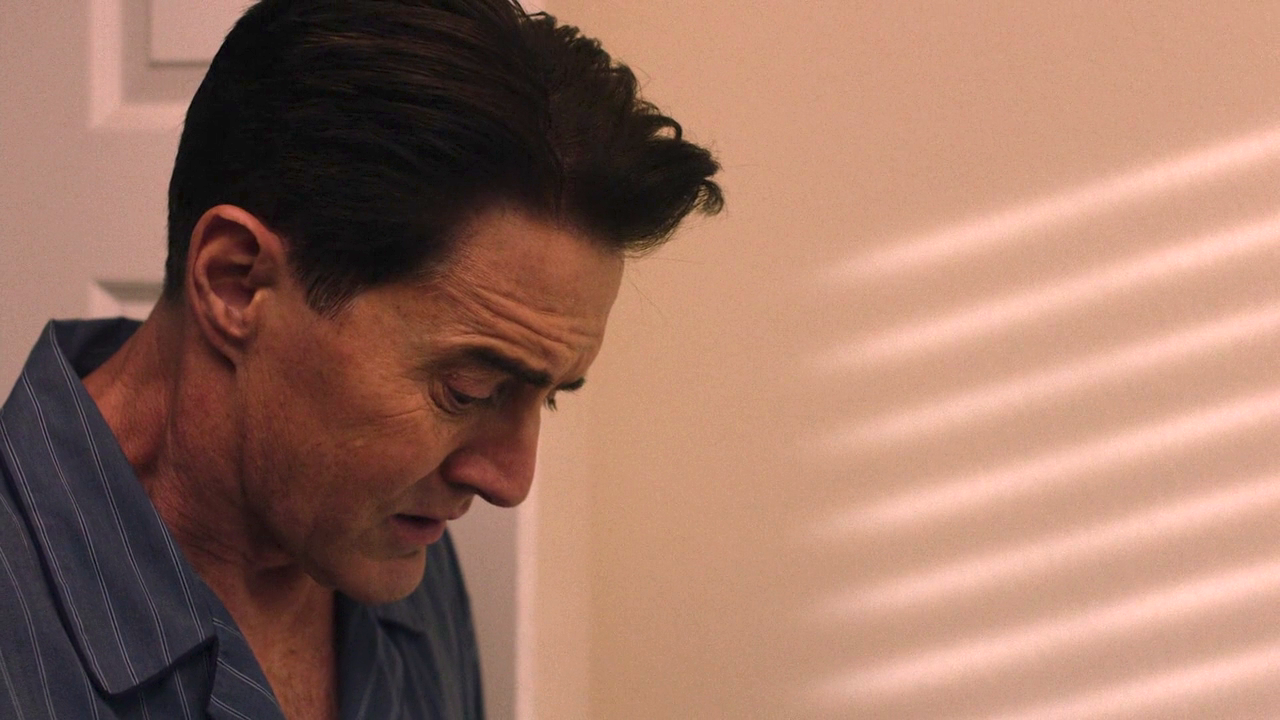

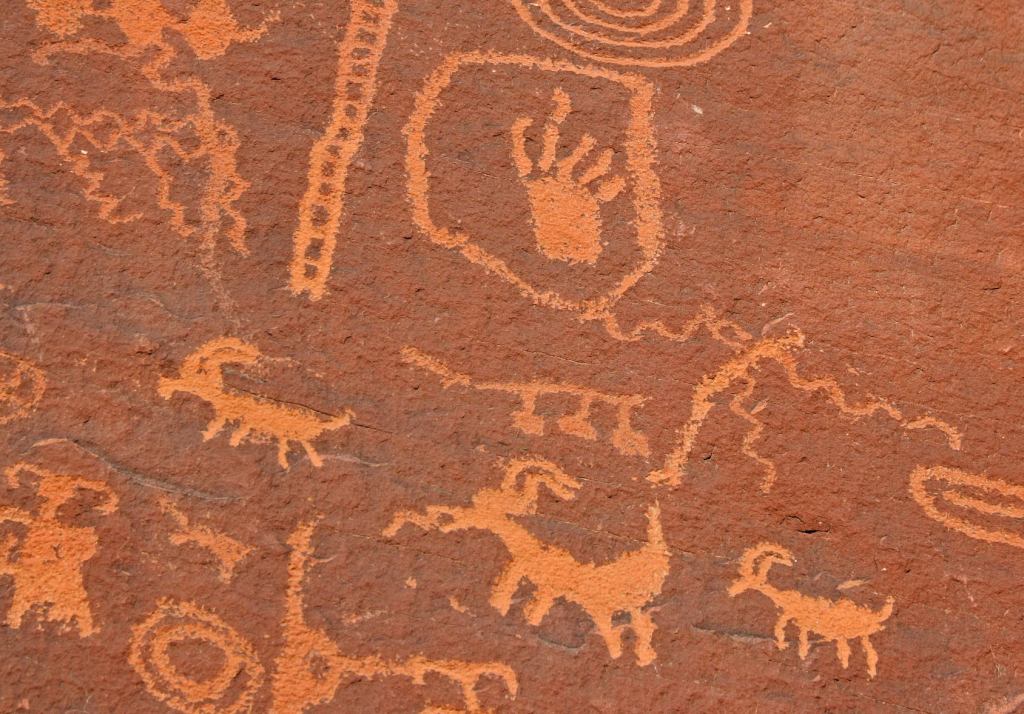

But since Ulysses chapter 4 is about the nymph Calypso, one might wonder who she might be in The Return. Odysseus spent 7 of his 10 years-long return trip to Ithaca in the arms of Calypso (“the Concealer”), on her island of Ogygia, where she offered him immortality if he remained with her. It is reasonable to consinder that Janey-E might be Calypso’s equivalent in season 3. First, she also lives in an island of sorts, Las Vegas, an oasis trapped in the midst of an ocean of deserts and sands (it’s worth mentioning here that Las Vegas is located close to a place called “the Valley of Fire”, where one can find petroglyphs not dissimilar to the onces Dougie traces on his Lucky 7 Insurance reports).

Then, like Calypso, Janey-E traps Cooper in a prison of love from which he will have the utmost difficulty to escape (while at the same time Mr. C goes to prison in Yankton, in a mirror situation to the one experienced by Cooper — at this point of the story, they are both in captivity).

This prison is reminiscent of the exile in Egypt that the Jewish people endured and many elements in season 3 point towards the role of Cooper as a new Moses, “returning” his people to the Promised Land. This echoes the Zionist leaflet Bloom is given in chapter 4, encouraging the colonisation of Palestine. Even though he is a secular Jew, Bloom cannot escape his identity. Similarly, Cooper’s past is slowly rising to the surface, until he finally “wakes up” in part 16.

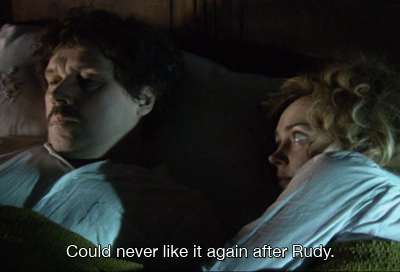

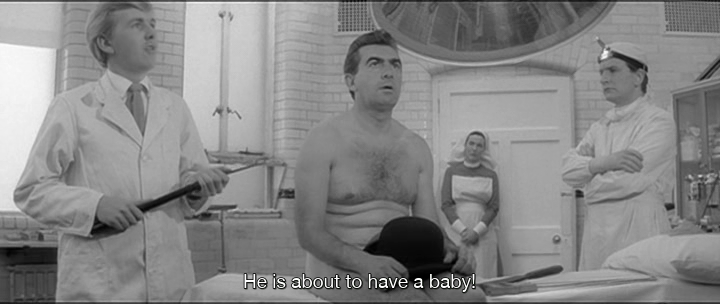

As far as Ulysses is concerned, this is the moment when Bloom serves breakfast in bed to his wife Molly (who grew up on the island of Gibraltar). Above their bed, there’s a painting called “the bath of the nymphs”, connecting this moment to Calypso. Janey-E is akin to Cooper’s wife in The Return — at least, she is Dougie’s wife. Nevertheless, while Bloom is the cuckolded in Ulysses, it’s Janey-E’s husband — the original tulpa Dougie Jones — who is seen in the arms of Jade in part 3 (concerning Cooper’s arrival in Rancho Rosa, note that In 1893-94, ten years before the present reality of Ulysses, Bloom worked as a clerk superintending sales in a cattle market; one may wonder if it’s not humans who play the role of the Rancho Rosa cattle). The usurper in The Return is Cooper himself, who acts as if he were the true Dougie Jones — he is the one who usurps another man’s home. And contrary to the death at 11 days of little Rudy in Ulysses, Bloom and Molly’s boy, Sonny Jim is alive and kicking in season 3. He is about the age Rudy would have been in Ulysses had he not died so young.

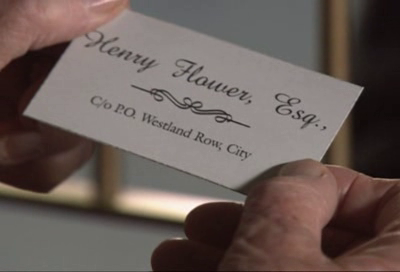

5- Lotus Eaters

Bloom’s dedication to his home and wife are tested in chapter 5 of Ulysses, as he is tempted to relax and do nothing, thinking about the languor of life in the Far East, the farniente of the land of the “Celestials”, taking a mental journey there in the context of a tea company. The chapter relates to the moment in The Odyssey when Ulysses and his men come to an island full of “lotus flowers” when they eat the fruit of the plant and just want to remain there, become indolent and stupefied, and forget about going home. Ulysses, who contrary to his men, does not eat the plant, does not forget his destination. He does not succumb to forgetfulness.

Interestingly, Bloom’s pseudonym in Ulysses is Henry Flower.

In season 3 of Twin Peaks, one should note Janey-E’s flower shirt (the language of flowers), but there are no roses without thorns: she too is a drug making Cooper forget about his true home.

Part 5 of The Return introduces us to a crowd of drug addicts seeking artificial narcosis. There’s Becky and Steven, of course, sniffing cocaine in front of the RR. There’s also the 119 woman, stuck in her Rancho Rosa home, unable to do anything outside of getting high. It’s their way to deal with frustrations and pains. “The chemist turned back page after page… Quest for the philosopher’s stone. The alchemists. Drugs age you after mental excitement. Lethargy then. Why? Reaction. A lifetime in a night. Gradually changes your character” (Ulysses).

To a certain extent, one could argue that Dougie Cooper is also part of the group with his addiction to coffee, though this is not enough to make him forget his home, as proved during the last sequence when he examines the shoes of the cowboy statue in front of the Lucky 7 Insurance building (they may represent “home” because of the shoes he left behind in Naido’s realm). If he does forget to come back to his Las Vegas home, that’s because he still remembers his true home, Twin Peaks.

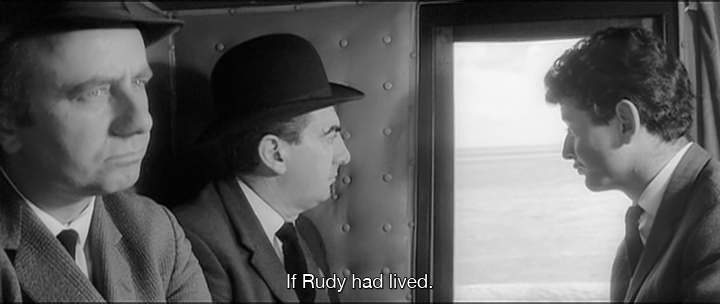

6- Hades

Hades, in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Joyce gave Hades name to the 6th chapter of Ulysses as Leopold Bloom accompanies a group of men to a cemetery in the northwest of Dublin, for the burial of someone they knew, Paddy Dignam, who officially died of a heart attack, but who really drank himself to death. The entire time Bloom remains mentally isolated from the others due to the inescapability of his Jewish identity.

Besides stressing the inescapability of death, this moment echoes Odysseus’s trip to the underworld, to the land of the dead, where he meets the shade of Tiresias, the blind prophet. Several moments in part 6 give us the feeling to be taking such a trip, but none as much as Richard’s exchange with Red, truly life threatening.

For the first time in the novel, there is a brief moment of convergence between Bloom and Stephen as the former sees the latter walking on the beach in the distance (see chapter 3, as the book’s events are not always diachronic). Also, before arriving at the cemetery, the funeral procession passes the coffin of a child : “A tiny coffin flashed by”. This leads Bloom to think of Rudy, his dead son, and to imagine what he could have become. He doesn’t brood about Rudy’s death, though, but celebrates his birth : “If little Rudy had lived. See him grow up. Hear his voice in the house. Walking beside Molly in an Eton suit. My son. Me in his eyes. Strange feeling it would be. From me.“

In addition to the relationship between Dougie Cooper and Sonny Jim, this is reflected in part 6 by the sequence when Richard runs over a child at a crossroad. The senseless violence of the moment underlines how fragile the links that unite us to our beloved truly are. “In the midst of life… we are in death”.

Ike the Spike’s bloody murders near the end of the episode are also evocative of the hellish nature of life in Las Vegas, plagued as it is by demonic entities. “Tomorrow is killing day… Roast beef for old England… All those animals could be taken in trucks down to the boats”. (Ulysses)

Bloom then reflects on the Christian doctrine of resurrection (Lazarus). For him, the human body is not the temple of the Holy Ghost, just a mechanical apparatus. This is his way to affirm the power of this life, the fertilising power of corpses giving life to other beings, in an endless cycle — the body lives on forever. The Return argues differently, as the child’s life force is seen rising up towards the sky above his corpse.

Just in case someone is buried too fast, Bloom nonetheless suggests putting a telephone in the coffin. This goes along with the discoveries of the time linked to the preservation of the human voice (gramophone) — listen to the sounds. “Have a gramophone in every grave or keep it in the house… Remind you of the voice like the photograph reminds you of the face”. (Ulysses)

The fact that Bloom’s father committed suicide is mentioned by several people during the procession: “But the worst of all, Mr Power said, is the man who takes his own life… The greatest disgrace to have in the family, Mr Power added”. This is echoed in The Return when Sheriff Truman’s wife has a breakdown, unable to get over the death of their son. Joyce argues that Christians have no pity for suicides and infanticides (does Bloom believe he killed Rudy? Is this why he hasn’t had sex with Molly for 10 years?).

7- Aeolus

The 7th chapter of Ulysses, out of order in relationship to The Odyssey, is about Aeolus, the King of Winds who lived on a floating island. It describes the second convergence between Bloom and Dedalus, at noon, in the offices of two Dublin newspapers, in the heart of the metropolis. Bloom is there doing his job and Stephen to deliver Deasy’s foot and mouth letter. Myles Crawford, the editor of the Evening Telegraph, blows Bloom off.

The chapter is a critique of journalism and rhetoric, intercut with impersonal headlines, that is to say with a language no one speaks. These break up the flow of the narrative into readily digestible bits. Part 7 of Twin Peaks plays with this notion after Ike’s failed attempt to kill Dougie in front of the Lucky 7 Insurance building. A television team gives a sensationalist account of what occurred with several interviews of witnesses that don’t really tell us much about the attack itself.

Journalism is described by Joyce as an impersonal, mechanical writing industry that differs from Stephen’s vision as an artist. There is no real human breath in the newspaper, no human voice, contrary to the short-story written by Dedalus about two middle-aged spinsters who climb Nelson’s phallic pillar, and eat plums while looking at his statue. This is meant to show how Ireland has lost its virginity to English power.

In this chapter, there is a description of the printing machines at work in the newspaper. Their impersonal repetitive qualities seem somehow antithetical to the work of a real writer: “Machines. Smash a man to atoms if they got him caught. Rules the world today”. This link between machines and atoms echoes the moment when Gordon is caught whistling in front of a (mechanical) reproduction of the Trinity Test explosion. A visual parallel is then created between Gordon and the figure of Aeolus, his whistling metamorphosing (a portrait of Franz Kafka faces him) into a blowing wind at the base of the nuclear mushroom. One may wonder: is he trying to blow the fire away or kindling it?

Other references to the powers of the wind can be found during part 7: Janey-E acts as her usual whirlwind in this episode, while Cole and his team fly through the air in their private jet, Beverly’s husband is attached to an air bottle, Mr. C and Ray leave the Yankton Federal Prison free as the wind.

In contrast, a lot of characters appear trapped inside their environment in part 7 : Jerry in the forest, Mr. C in the prison, Beverly Paige in her relationship with her sick husband… Perhaps this reflects the tale told in Ulysses about the Egyptians trying to persuade the Jews to give up their ways and reject liberation from their house of bondage : “Israel was weak and few are her children; Egypt is an host and terrible are her arms… he would never have brought the chosen people out of their house of bondage nor followed the pillar of the cloud by day”. Only Cooper/Moses is able to free his people. But at this point in the story, he still needs to wake up himself. Nonetheless, at the end of part 7, both he and Mr. C are leaving prison, the latter literally and the former with his memories beginning to return.

Finally, another reference to Theosophy in this chapter of Ulysses : “What do you think really of that hermetic crowd, the opal hush poets: A. E. the master mystic? That Blavatsky woman started it”.

8- Lestrygonians

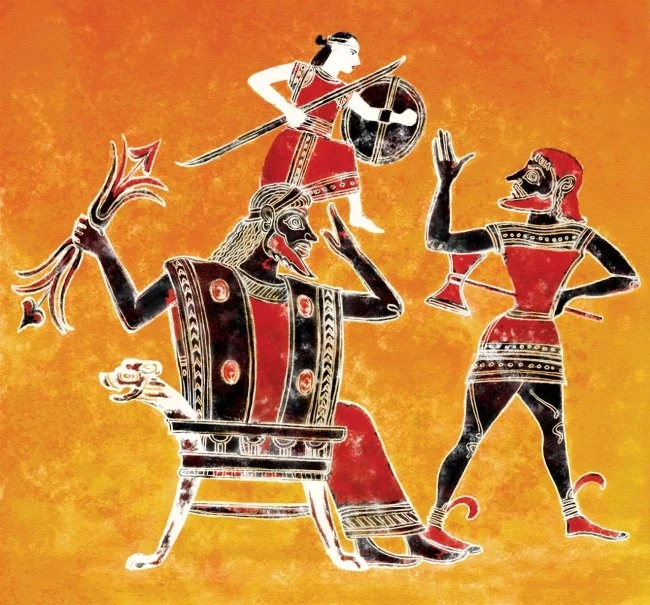

I am a bit atypical in the sense that I tend to prefer part 3 to part 8 of The Return, more diverse and experimental in my opinion, but there is no denying that part 8 is an important moment in the recent history of television. It corresponds to the eighth chapter of Ulysses, named after the Lestrygonians, giant cannibals who destroy most of Odysseus’s ships by throwing huge boulders at them, slaughtering their crews. Only Odysseus and his crew manage to escape the massacre.

In the novel by James Joyce, it’s 1 p.m., lunchtime, and Leopold Bloom looks for a place to satisfy his hunger. As made clear earlier, Bloom loves food, but he is disgusted by the animalistic way that the customers are eating in the first restaurant he stops at — leaving, he feels he has escaped from cannibals. Interestingly, he somehow links cannibalism to sexual potency, which reminds him of the fact that he hasn’t had sexual intercourse with his wife since the death of their son ten years ago. Meanwhile, he is eaten alive by the memory of Blazes Boylan cuckolding him with Molly. He nonetheless finds the time to feed a flock of gulls bits of cake — as a benevolent deity, something reminiscent of the mana the Israelites were given as they were starving in the desert, during Exodus ; this desert is echoed in part 8 with New Mexico — on route to see statues of Gods, so as to better digest. The Gods have nothing to do with excrement because they have no anus. Bloom sees the whole of life as a digestive cycle going nowhere. We are born to be devoured by death.

It might not be evident at first, but there is a lot about Gods, sexual potency, and eating in part 8 of The Return. First, the Trinity Test explosion is a clear phallic symbol illuminating the sky of New Mexico. It is a “let there be light!” moment, usually ascribed to a male deity — not a moment of creation in this case, but of destruction. Toxic masculinity actually plagues many portions of The Return, and this might be its archetypal summit.

It is followed by another phallic symbol, the peak in the middle of the purple ocean, but this one leads to a non threatening male figure, that of the godlike Fireman. No toxic masculinity there but a desire to extinguish passions on the contrary, to blow out the fire ravaging the world.

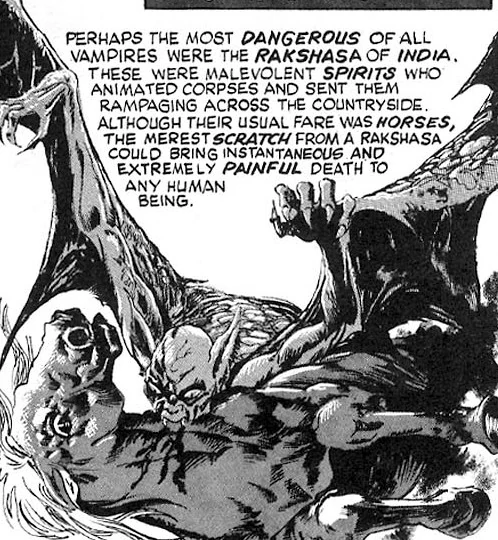

As for eating and cannibalism, it might not seem evident at first, but I believe this is what takes place when the Woodsman lays his hand on the head of his victims — he feeds on them, on their blood. This vampiric mode of feeding is evocative of the way Rakshasas, Hindu demons with long beards, are said to proceed. They are most often depicted as shape-shifting monstrous-looking creatures, with two fangs protruding from the top of the mouth, with claw-like fingernails. These insatiable man-eaters that can smell the scent of human flesh, drink blood with their cupped hands or from human skulls (similar to representations of vampires in later Western mythology). Generally they can fly, vanish, and have maya (magical powers of illusion).

The Woodsmen are basically the equivalent of the Lestrygonians in The Odyssey.

As far as eating is concerned, there is also the scene with the Frogmoth, which carries a strong sexual undertone of rape, the ingesting of the viscous beast taking place as the young Sarah Palmer is unconscious.

Of course, what comes in must eventually come out, and though we do not see a deity excreting in part 8, we do see one vomiting (in a moment highly reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp’s famous work The Bride and her Suitors, even), likely a result of the Trinity Test explosion. But this vomiting is akin to giving birth as well — many eggs can be seen floating in the gelatinous substance (the Milky Way, according to Duchamp) released by the Experiment in space.

How does this relate to Ulysses?

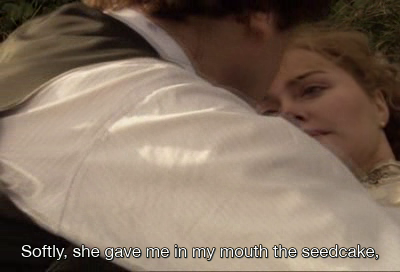

In Chapter 8, Leopold Bloom enquires about a woman who now has been in childbirth labor for three days. He shows much compassion for her suffering. He also remembers the first time he made love to Molly. Interestingly, this first time mixed the pleasures of sex and eating, as they shared food while they kissed and he made love to her as if he were eating her. These two pleasures are interchangeable in his mind, joyous consummation. But the memory also leads him to think about Rudy’s death. From food, to sex, to giving birth, to death. After the death of his little boy, Bloom never managed again to enjoy sex. This event left a gulf between his past and present self.

In part 8, several sequences are evocative of childbirth : there’s the moment mentioned above when the Experiment vomits a large number of eggs; there’s also the scene when the Fireman “summons” Laura’s orb/pearl out of the lips of a golden vagina/seashell; but one should not omit Mr. C’s near death experience, when the Woodsmen act as midwives around him, while BOB’s orb almost leaves Mr. C’s “womb” in a bloody caesarean section — the woodsmen even hold Mr. C’s head up, so that he can admire “the fruit of his womb”.

9- Scylla and Charybdis

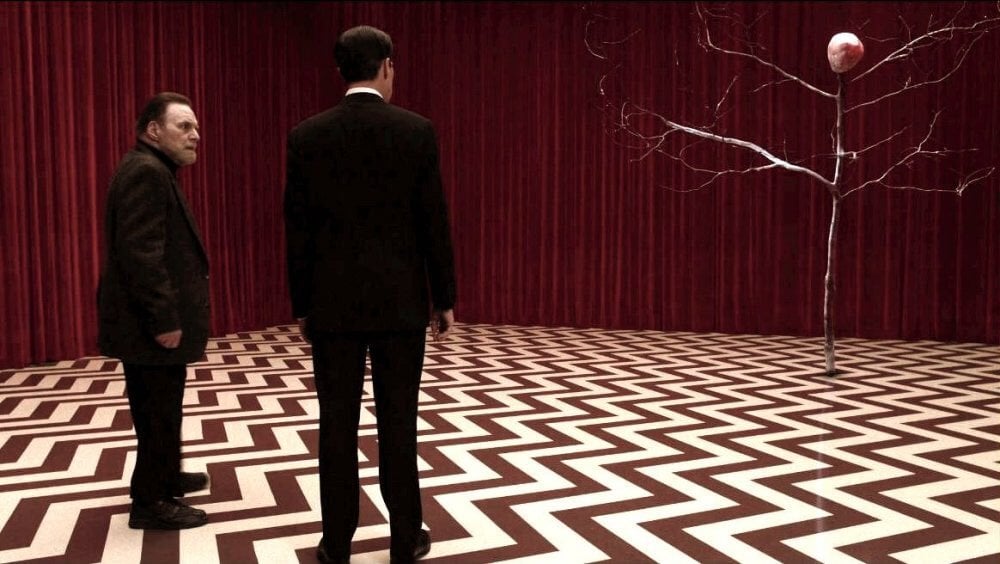

Chapter 9 of Ulysses takes place in Dublin’s National Library, where Stephen delivers another of Deasy’s letters. There, he becomes a storyteller, expounding his theory about Shakespeare’s Hamlet to a group of friends, among whom the Theosophist George Russel (many references are made during this chapter to esotericism, creating a clear link to the Twin Peaks universe : “The beautiful ineffectual dreamer who comes to grief against hard facts”; “Seven is dear to the mystic mind. The shining seven”; “Brothers of the great white lodge always watching to see if they can help”; “Hold to the now, the here, through which all future plunges to the past”; “So in the future, the sister of the past, I may see myself as I sit here now but by reflection from that which then I shall be”). Stephen argues that Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets express his life.

His argument basically goes as follows : Hamlet’s father was murdered by his uncle, and his ghost appears to his son to ask for vengeance. “What is a ghost? Stephen said with tingling energy. One who has faded into impalpability through death, through absence, through change of manners. Elizabethan London lay as far from Stratford as corrupt Paris lies from virgin Dublin. Who is the ghost from limbo partum, returning to the world that has forgotten him? Who is king Hamlet?”. Here is the usurpation theme once more, as well as the father-son relationship, similar to The Odyssey.

According to Stephen, Shakespeare is the ghost (king Hamlet) talking to his dead son Hamnet (who died at 11 — years, not days). He argues that Anne Hathaway, his wife, committed adultery with one of his brothers when he was gone for 20 years. “The theme of the false or the usurping or the adulterous brother or all three in one is to Shakespeare, what the poor is not, always with him. The note of banishment, banishment from the heart, banishment from the home”.

Cooper too was gone for more than 20 years, trapped in the Red Room, and Dougie is the ghost of who he was. He regularly sees ghostly hints of his previous life. After all, what is a revenant if not a returner? He was banished from the Lodges and now he longs for a return to the womb.

Bloom is basically Stephen’s surrogate father, which makes him Shakespeare to Hamnet/Hamlet. The two notice each other for the first time in this chapter. Mulligan also calls Bloom “the wandering Jew”. He is akin to Odysseus “sailing” the strait between the two dangers of Scylla (the she-monster who lives in a cave, with 6 heads = self-facts, matter // Aristotelian materialism: “hold to the now, through it, all future plunges to the past”) and Charybdis (the whirlpool = of formless spiritual essences, self-absorption // According to Russel, a neoplatonic, art should be mystical, about formal essences, similar to Plato’s world of ideas… dreamy mysticism, stuck in the past)).

In other words, he neither falls into intellectualism or sensuality, journalism or the Irish Literary Revival (Yeats and Russell).

In a sense, similar to Shakespeare, he is banished from his home for the day, while Stephen has to leave the Martello tower — this echoes Cooper, who was banished from the Red Room.

Shakespeare avoided the dangers of pure materialism and pure essentialism by fusing the subjective life with the objective world (neither Scylla nor Charybdis). His art reflects both himself and the world: “He found in the world without as actual what was in his world within as possible… Every life is many days, day after day. We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love. But always meeting ourselves. The playwright who wrote the folio of this world… is doubtless all in all in all of us”.

Mulligan makes fun of this pretention : “Himself his own father, Sonmulligan told himself. Wait. I am big with child. I have an unborn child in my brain. Pallas Athena! A play! The play’s the thing! Let me parturiated!”. Athena was the guardian angel and patron saint of Odysseus and his family in The Odyssey. She was supposedly born from Zeus’ forehead by parthenogenesis — which echoes the way The Fireman gives birth to Laura in part 8.

Stephen is the Icarus whose only flight was to Paris: “Fabulous artificer, the hawklike man. You flew. Whereto? Newhaven-Dieppe, steerage passenger. Paris and back. Lapwing. Icarus. Pater, ait. Seabedabbled, fallen, weltering. Lapwing you are. Lapwing he”. Even Mulligan calls him a bird: “Come, Kinch. Come, wandering Aengus of the birds” (Irish god of beauty, youth, and love. Continually in search of his ideal mate, who had appeared to him in a dream).

10- Wandering Rocks

The next chapter of Ulysses sees the various characters leave the National Library into the labyrinth of Dublin, in which they bump into each other. The chapter is conceived spatially in 19 sections focusing on various aspects of life in Dublin, without any apparent order – the great machine of the city is turning its wheel. Thanks to the advice of Circe, Odysseus avoids the wandering rocks, supposedly somewhere in the Bosphorus (here akin to river Liffey), between Europe and Asia, impossible to negociate. The novel is full of stories that don’t really have endings, resolution, which is very much alike what takes place in The Return.

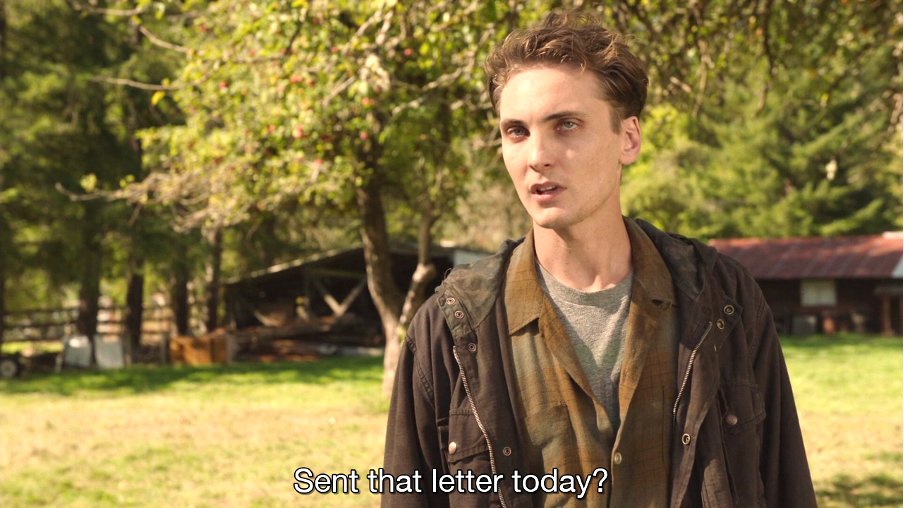

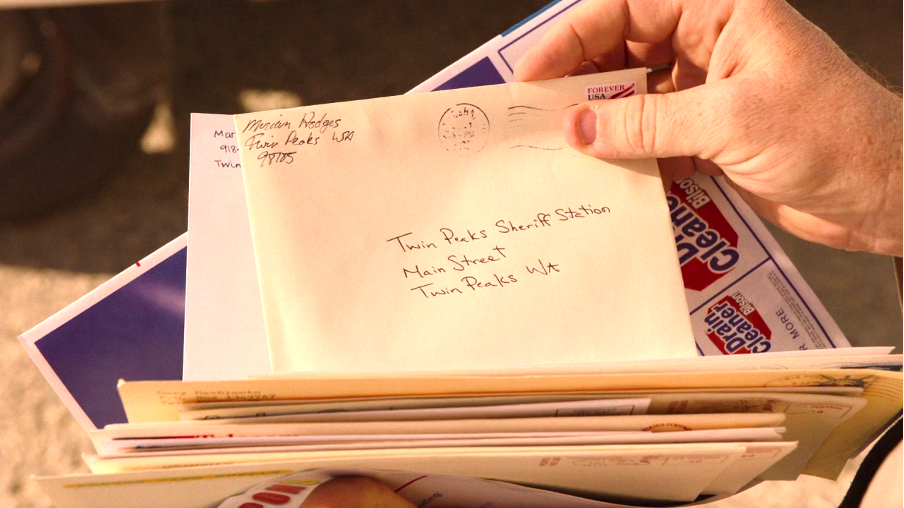

The chapter begins with a letter to be posted, which echoes the one Richard intends to stop in part 10.

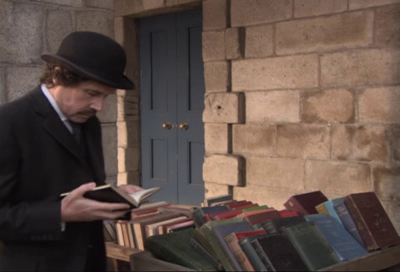

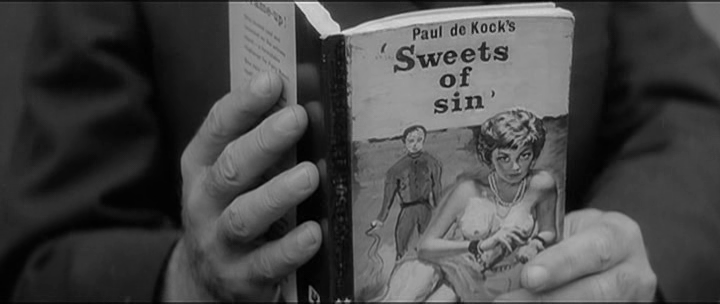

Among other things happening, Bloom buys a book for Molly, Sweets of Sin (a woman who cheats on her husband — “He read the other title: Sweet of Sin. More in her line. Let us see”).

It is clear that he is not the typical cuckold; a conversation about his knowledge of astronomy also takes place (“Bloom was pointing out all the stars and the comets in the heavens to Chris Callinan… But, by God, I was lost, so to speak, in the milky way. He knows them all, faith”).

The chapter also describes Blazes Boylan buying pears and peaches for Molly; Stephen, scanning books, meeting his poor sister, another drowning woman he cannot save — their father Simon has given up his responsibilities and he therefore searches for a surrogate one; meanwhile, a paper boat is floating down the river…

Mostly, part 10 resonates with chapter 10 in the way characters “bump” into each other, often in a violent manner. They are the dangerous wandering rocks, always ready to sink each other’s boats.

Besides the fact that one notes a mention to a Sycamore Street in the chapter, one last segment is of interest in relationship to Twin Peaks, when the following sentence is read: “I between them. Where? Between two roaring worlds where they swirl, I”.

Between two worlds is a recurring motif in the series, of course, and it’s interesting to link this to the two following quotes: “Wandering between two worlds, one dead, / The other powerless to be born” (Matthew Arnold) and “We have two lives about us, / Two worlds in which we dwell, / Within us and without us, / Alternate Heaven and Hell:– / Without, the somber Real, / Within, our heart of hearts, / The beautiful ideal” (Richard Henry Stoddard).

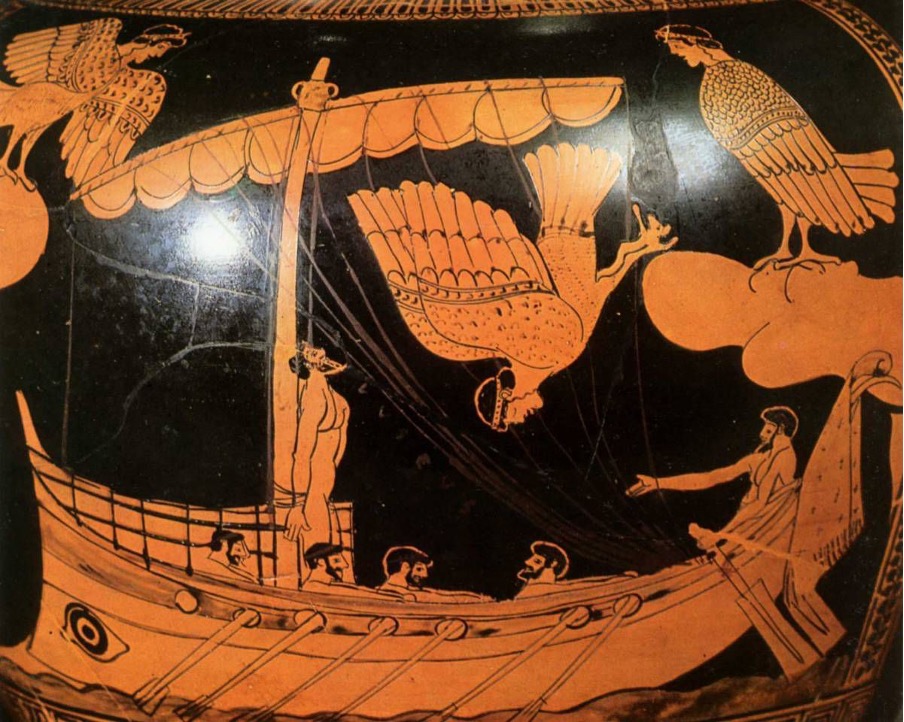

11- Sirens

Set in Dublin’s Ormond hotel, chapter 11 is centred around music and one song follows the other, music recreated into words on the model of a fugue (Subject / Answer / Countersubject / Climax / Coda). Music is used as a way to seduce, just like Molly uses her voice to catch Boylan. This refers to the moment in The Odyssey when Odysseus meets the sirens, who lure men to their island. He manages to resist their call because he asked to be tied to his ship’s mast while the ears of his men are stuffed with wax. The sirens of chapter 11 are the barmaids of the hotel. Bloom, while he writes a letter to his secret lover Martha, resists a song about a martyr from the Irish revolution. He shares Ulysses’s will to hear and taste everything, but music never puts his mind to sleep. One could argue that singing is a kind of drunkenness.

While there is no actual singing in part 11, there is music in its last section when the Mitchum Brothers offer Dougie a meal to thank him for the check he’s given them — and the nostalgic music (“nostos”, the root for nostalgia, is a theme used in Ancient Greek literature, which includes an epic hero returning home by sea) does catch his attention, bringing on memories to his mind. The arrival of Candie and her two pink companions is reminiscent of the waitresses/sirens at the Dublin’s Ormond hotel.

Bloom’s final homecoming is prefigured by the many homecomings of his thoughts. The same goes for Cooper.

One of the sirens, Ligeia, was known as “the one who utters a piercing cry”. This might very well apply to Becky and her mother Shelly, who are both seen shrieking during part 11. In Edgar Allan Poe’s eponymous short-story, Ligeia is also seen shrieking: “”O God!” half shrieked Ligeia, leaping to her feet and extending her arms aloft with a spasmodic movement, as I made an end of these lines –“O God! O Divine Father! –shall these things be undeviatingly so? –shall this Conqueror be not once conquered?”.

Finally, one might wonder if the sequence when Gordon almost gets sucked into the sky whirlpool is not also a reference to the sirens. Even though his ears are “stuffed with wax” (his hearing apparatus functions occasionally at best), he seems to succumb to the call of the Woodsmen. If Albert hadn’t caught him before it was too late, Gordon might have been swallowed by their Charybdis-like vortex.

12- Cyclops

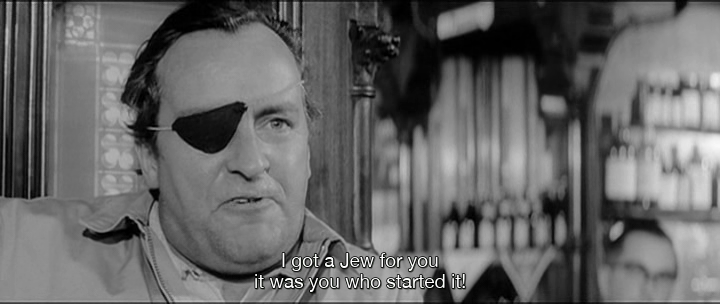

While Odysseus met the original cyclops Polyphemus in his cave, where he liveed isolated with his livestock, chapter 12 takes us to a pub where the monster’s equivalent is a myopic and xenophobic character called the Citizen, surrounded by a pack of Irish men/sheep. Part 12 of The Return also begins in a bar.

But as in the 2003 (Bloom) and 1967 (Ulysses) filmic versions of the novel, when we get to meet the true one-eyed cyclops — the one throwing rocks at Odysseus’s ships as they leave / a biscuit tin at Bloom’s head as he escapes — the Citizen becomes a one-eyed man in The Return. In season 3, the evil racist Citizen is replaced by Hutch killing the Yankton prison’s warden from a distance, his right eye becoming enormous through the rifle’s telescope. It’s worth noting that Hutch and Chantal are hardly brighter than the original Cyclopes, but just as dangerous.

He is not the only one throwing something at someone else, as Dougie Cooper himself becomes the target of another throw of a lesser magnitude, Sonny Jim trying to play catch with him, hitting him in the head with his ball.

This is all of course out of order compared to The Odyssey, as Odysseus’ curse is a direct result of his encounter with Polyphemus, at the very beginning of the story. His ten-year long return journey is caused by this initial encounter.

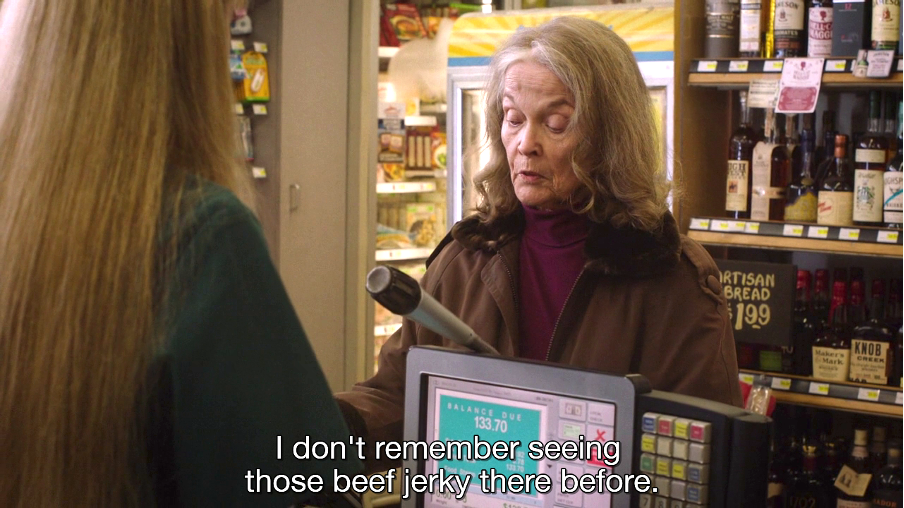

Meanwhile, everyone eats from other people’s flesh like cyclopes : Kriscol from the Fat Trout Trailer Park sells his blood to get money, and Sarah Palmer gets upset when she sees a new set of beef jerky at the drugstore. Hutch and Chantal can’t wait to be done with their assassination of the warden to go eat at Wendy’s.

To close this section, let’s not forget two other “cyclops” of sorts: James Joyce himself and Nadine Hurley.

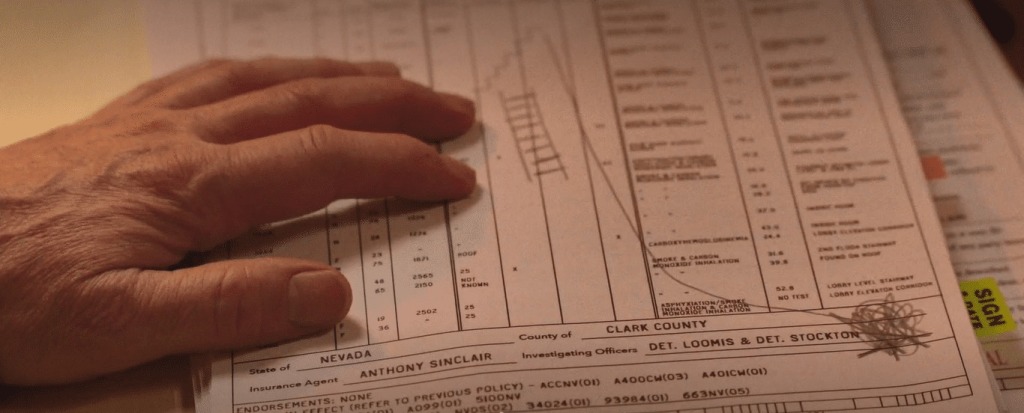

13- Nausicaa

In this chapter, Bloom goes to the beach at Sandymount, literally walking in Stephen’s footsteps (see chapter 3). He has just taken care of Dignam’s insurance money, the friend to whose funeral he went in part 6 — which echoes Dougie Cooper’s job at Lucky 7 Insurance. This visit to the beach resonates with Odysseus’s arrival on the island of Phaecia, when he meets Nausicaa, daughter of King Alcinous. She is there with other women, washing clothes and playing ball. She gives him things to wear, food and a bath. Later on, she tempts him to stay with her, to forget about Penelope — but nothing happens between them.

Her equivalent in Ulysses is named Gerty McDowel, who is on the beach with several girlfriends and children playing ball. She and Bloom only look at each other from a distance, but while fireworks are being shot in the sky, she leans back and exposes herself to him. These sexual fireworks lead Bloom to turn into a voyeur and a masturbator, releasing some of the tension accumulated thus far. When she leaves, he notices that she’s lame and he feels empathy for her.

That’s the point at which he notices that his watch has stopped at 4:30, the precise time when his wife Molly and Blaze Boylan must have consummated their affair. I have already discussed the importance of this moment in relation to The Return when analysing the first part of the season.

In part 13, there are reasons to think that Leslie, the waitress working at Szymon’s Famous Coffees, located near the entrance of the building hosting the Lucky 7 Insurance offices, plays a role similar to that of Nausicaa’s. Like her, she brings food and a drink to Cooper. Her general attitude towards him is extremely motherly (Leslie means “holly-garden”), which is also true of Homer’s Nausicaa. Besides, Szymon’s is clearly connected to the Red Room (home?), as exemplified in part 11, when MIKE calls Cooper from the shop so that he buys a cherry pie for the Mitchum Brothers. This saves his life, and similarly, his actions with Leslie might also have saved him from Sinclair’s poisoning.

Before leaving the beach, Bloom traces a few words in the sand, a message to Gerty if she comes back the day after. And then he realises that it will get washed out by the tide and stops. He only draws: “I am a…”. This could mean that he defies characterisation, being a complex human being; this could also mean “I am A/Alpha”, the first letter of the alphabet — there are reasons to believe that Laura/Carrie might be his “Omega”, as proven by her necklace in part 18, an inverted horseshoe that could be read as the Greek way to write the symbol.

14- Oxen of the Sun

The next chapter of Ulysses takes place at the National Maternity Hospital, where Bloom comes to enquire about how Mina Purefoy — the woman who has been in labor for three days — is doing. He finds out that she has finally given birth. In the visitor’s waiting room, he meets Stephen among friends, and he develops paternal thoughts about him, convinced that his drinking and partying are killing the young man’s creative energy.

These considerations about childbearing and creation echo the portion of The Odyssey centered around Helios, the God of the Sun. Circe and Tiresias had warned Odysseus of disaster if he came to his island. He was told not to slaughter any sheep or oxen while on the island. But when his crew runs out of Circe’s food, they start feasting on Helios’s cattle. As a result, a storm sinks everyone but Odysseus who, grasping his ship’s mast, drifts to the island of Calypso.

How does this relate to part 14?

The equivalent of Helios in this episode is The Fireman. Their relationship to fire is self-explanatory. The Fireman is also akin to Ra, in Egyptian mythology, another Sun God.

The disobedience of Odysseus’s crew, their killing of Helios’s oxen, is a crime against fecundity. Stephen defends creation of human life against men who only want to copulate. Stephen and Bloom are friends of cattle, i.e. they support life and fertility, and attack the use of contraceptives. They are apostles of creation.

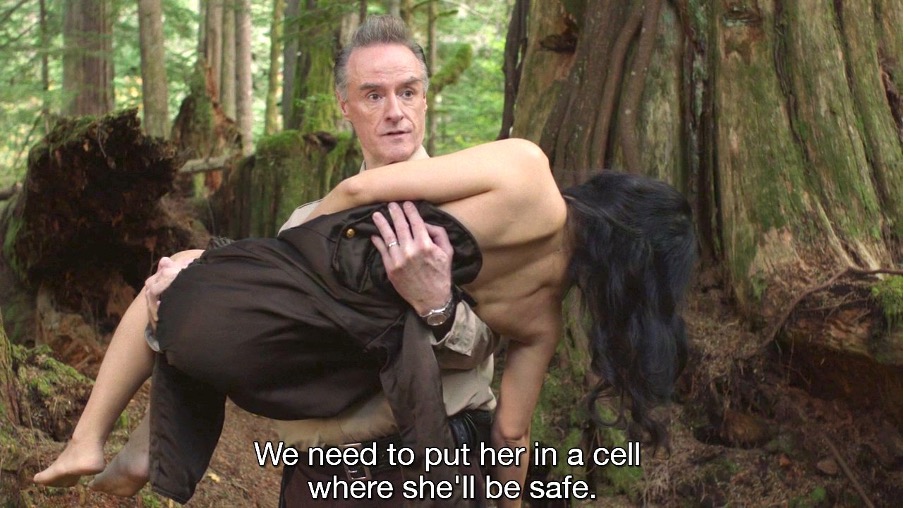

In The Return, The Fireman tells Andy to protect Naido, found alone and naked in the forest. She might very well be the cattle that needs protection from the forces of evil — those that ranch human beings in Rancho Rosa, turn cows into Beef Jerky, and send containers via train up to Odessa and Judy’s diner there.

15- Circe

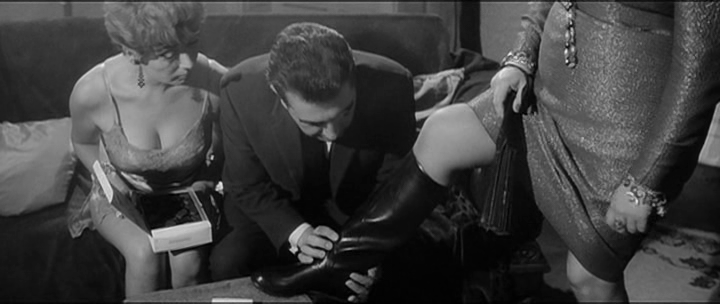

After their stay at the National Maternity Hospital, as the bell strikes midnight, Stephen heads for Dublin’s red-light district. Joyce turns the story into a gigantic play, full of hallucinations, kaleidoscopic transformations, a funhouse of mirrors. The chapter corresponds to the time spent by Odysseus with Circe, the enchantress. In The Odyssey, he does not succumb to her magic thanks to moly, a magical herb that protect him from her powers. In Ulysses, the moly becomes a potato — first, Bloom gives it up and is overwhelmed by hallucinations, which stop altogether when he recovers the potato. Zoe, one of the girls, first takes it from him, his talisman, an heirloom inherited from his mother, a hard black shrivelled potato (perhaps a reminder of the Irish potato famine?). Doing this is akin to giving up his manhood, to symbolically becoming castrated. As soon as he gets it back, though, he does his best to protect Stephen when the latter risks being overcharged (and later arrested). He frees him and manages to bring him “home”.

Circe’s equivalent in Ulysses is named Bella Cohen. She is a massive woman with a moustache. A complex transsexual relationship with her takes places in the chapter, as Bloom first kneels down to lace Bela’s boot, who then becomes Belo, turning Bloom into a sow, made to submit, animalised and emasculated. Though he eventually recovers himself and his manhood at the end, beginning to act like a father to Stephen and standing up to Bela, the chapter reveals the extent to which he can be described as a “womanly man”, dreaming of having a son, womanly in his care for other people. Bloom’s transexual hallucinations at Bella’s are also reminiscent of the bosomy woman welcoming Mr. C at the entrance of Philip Jeffries’ room (played by a man).

Mr. C’s “pregnancy” has already been discussed above. It is worth noting that it is also in part 15 that he meets his son Richard for the first time, as he is expelled from the room with Jeffries via the telephone line.

The corresponding figure to Circe in The Return appears to be the new version of Philip Jeffries. Trapped in room 8 of the hotel “behind” the convenience store, he works his magic from this place. The fact that Bela becomes Belo in Ulysses might explain why Philip turns into Circe.

Before he enters the realm of Jeffries/Circe, Mr. C is welcomed by a Woodsman holding a staff. In Joyce’s book, mention is being made of the Black Rod, an official in the parliaments of several Commonwealth countries, meant to keep order during their meetings.

Also, the Flying Dutchman (another “returner”) is mentioned for the first time in chapter 15 of Ulysses. Likewise, part 15 is the first time Cooper (as Mr. C) goes to the Dutchman’s: “These Flying Dutchmen or lying Dutchmen as they recline in their upholstered poop, casting dice, what reck they? Machine is their cry… laboursaving apparatuses”. The convenience store appears and disappears like a ghost ship, in a thick cloud of smoke.

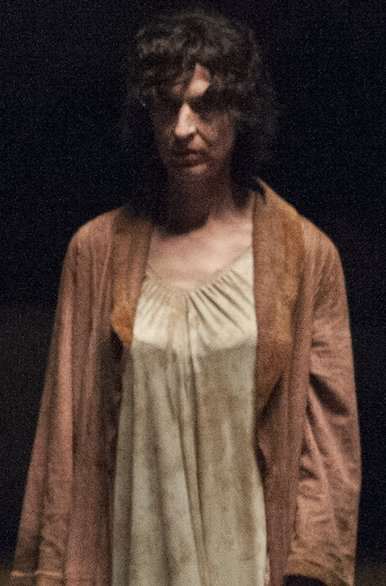

A variety of spectral accusers and tormentors manifest themselves to Bloom during the chapter, from his wife Molly to former flames, Martha Gerty, his former servant, etc. Even more ghostly, an emaciated figure rises from the floor — the spectre of Stephen’s mother, devoured by the crab of cancer. Difficult not to make a parallel between this apparition and the last of the Log Lady’s, in part 15, another motherly figure victim of cancer. When she dies, all the characters of Twin Peaks become orphans of her presence.

Horns are traditionally the sign of a cuckold and in chapter 15, Bloom’s head is antlered as he watches Boylan with Molly in a vision. This is probably a form of psychological defence on his part, punishing himself, repressing a sense of self-loathing. It’s important to recall that while they were having their affairs, he was masturbating on the beach. In English, to wear the horns means to be cuckolded because a horned beast cannot see its own horns — or perhaps this is an allusion to the mating habits of stags, who forfeit their mates when they are defeated by another male. In part 15, it makes sense to see a deer’s head in the background in the scene between Ed and Nadine, when she releases him from her bond.

Finally, there’s one last parallel between chapter 15 and part 15 that should be noted: in Ulysses, at the end of chapter 15, Stephen is knocked unconscious by a private (Stephen is a pacifist, he refuses to fight the privates from the British army), while at the end of part 15 of The Return, Cooper electrocutes himself unconscious. Similarly, Freddie knocks unconscious two men at the Bang Bang Bar.

Concerning Cooper’s electrocution, it might also be linked to Bloom’s immolation with a bag of gunpowder, carbonised, while an Apocalyptic passage in the book describes Dublin burning and the dead arising.

NOSTOS

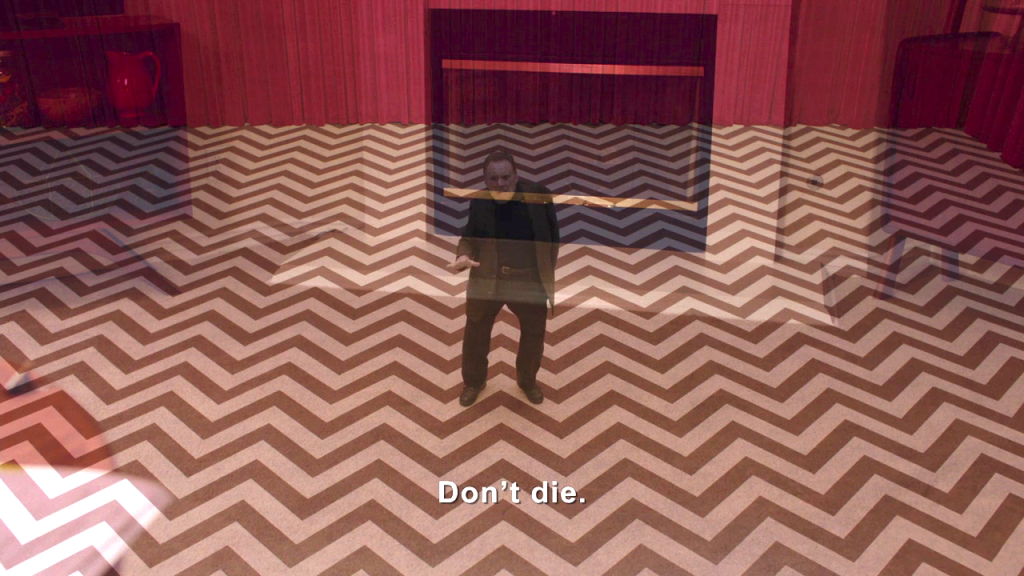

16- Eumaeus

Chapter 16 is the first step of the return to Ithaca. Ulysses and Telemachus are not totally one yet.

It’s now 1 o-clock in the morning on Bloom’s day/night and Bloom finally gets to talk with his surrogate son, Stephen. They go to a cabman’s shelter run by Skinny-the-Goat, an ex-convict, who serves them coffee. There, they meet Murphy, a sailor with the face of a Greek sailor tattooed on his chest, who spent seven years away from his wife, and tells many stories of his travels — this pseudo-Ulysses sometimes feels more Ulyssean than Bloom, but it’s an illusion.

In The Odyssey, Eumaeus was a kindhearted swineherd on Odysseus’ estate, who received his incognito master with hospitality. In his hut, the latter tested Telemachus’s filial commitment and then revealed himself. Bloom and Stephen repeatedly fail to understand each other in chapter 16, but there are nonetheless moments of real communication between them. At the very least, Bloom is not dismissed for his Jewishness by Stephen, like he was by so many other people on that day.

In part 16, at night, Mr. C and Richard reach the place corresponding to one of the sets of coordinates, and Richard climbs on a huge rock to the exact location. When he gets there, he gets electrocuted and disappears in flames. Before he does the climbing, though, Mr. C lets him know that he is 25-years his senior, and right after his death, he says goodbye to his son.

This sequence is of course a mirror image of what takes place in chapter 16. Even though this is indeed the beginning of the return to Ithaca / Twin Peaks for Mr. C (paralleling Cooper’s awakening in the same part), no true exchange or discussion take place between father and son, and Mr. C displays absolutely no feeling of loss when Richard dies. This is also the complete opposite of what happens when Cooper leaves Janey-E and Sonny Jim — he acts as a true husband/father with them, even though they are Dougie Jones’s family in reality.

As far as Eumaeus himself is concerned, his equivalent in part 16 is probably Bushnell Mullins. He has taken care of Cooper like a father for the whole duration of his stay in Las Vegas. Cooper, like Odysseus, was incognito, but that didn’t stop Bushnell’s sense of hospitality. He took care of him as if he had been one of his herd.

17- Ithaca

The penultimate chapter of Ulysses sees Bloom and Stephen finally reaching Ithaca, i.e. their true home. They sit in Bloom’s kitchen for a while, chatting about various subjects (among others the similar fates of the Irish and the Jews, both persecuted), bonding, drinking cocoa in communion (there’s something Christ-like about Bloom — the Christ’s human nature came from Jewish ancestors). Bloom would like to make Stephen part of his family, but Stephen declines as this would essentially mean sacrificing his literary ambition. All this echoes Odysseus’s arrival at his palace in Ithaca. Bloom who forgot his house key enters via a stratagem, like Odysseus who disguised himself in order to get close to his wife’s suitors. Both Bloom and Stephen can be described as keyless — Bloom even lost his key to Molly’s lock, and he finds his place usurped by Blaze Boylan.

In part 17, both Cooper and Mr. C make it back to Twin Peaks, their own version of Ithaca. Mr. C, like Odysseus, can also be said to be in disguise, pretending to be the real Cooper until Sheriff Truman unmasks his deception and Lucy shoots him dead. Their “encounter” is quite short, like the one between Bloom and Stephen, and it does not take long before one of them disappears — Stephen leaves Bloom’s house, while Mr. C is taken to the Black Lodge thanks to the owl ring. Cooper thus retakes possession of his “house” in Twin Peaks, getting rid of the usurper.

Shortly beforehand, Freddie Sykes boxes BOB’s globe into little pieces. Could this floating rock have something to do with comets, said to be “hirsute” because the word comet derives from the Greek kometes, “having long hair”?

The second half of chapter 17 is dedicated to Bloom’s return to his bedroom, where Molly is waiting for him. It’s his real homecoming, his return to the marital bed — he lies with his head at Molly’s feet, back to his point of departure, opening up to the infinity of space and time. Contrary to Odysseus, he seeks no violent revenge and achieves equanimity.

This portion echoes the fact that Odysseus built his bed around the trunk of an olive tree, a fact used by his wife Penelope to make sure that he truly is who he says he is. The question concerning The Return is whether Molly/Penelope is supposed to be Diane or Laura. Cooper tries to play the role of Moses with the latter, bringing her out of the House of Bondage (Egypt) and back to the Holy Land (Twin Peaks). But isn’t her true House of Bondage the one in which she grew up? And isn’t Cooper’s love affair with Diane made evident in part 17, in the Sherriff’s office?

If one is to decide based on the fact that Diane and Cooper kiss in part 17, it should be remembered that Cooper and Laura also kiss in the Red Room. I would personally suggest that Diane is more akin to a wedding with the anima side of his personality (she disappears after they have communed in sex magick), whereas Laura would be something of a spiritual bride that transcends this earthly realm. Diane feels like a late addition to the mythology of Cooper’s sentimental life, as we have never seen her prior to this season. On the other hand, it’s clear that he is obsessed with Laura and shares a transcendental bond with her.

If history is repeating itself with a difference in Ulysses, where Bloom reenacts the major events of Ulysses’s odyssey, Cooper is about to start a spacetime loop with his decision to bring Laura back from the dead.

Before moving on to the last portion of Ulysses and The Return, note the similarity between Bloom’s pot and the new version of Phillip Jeffries.

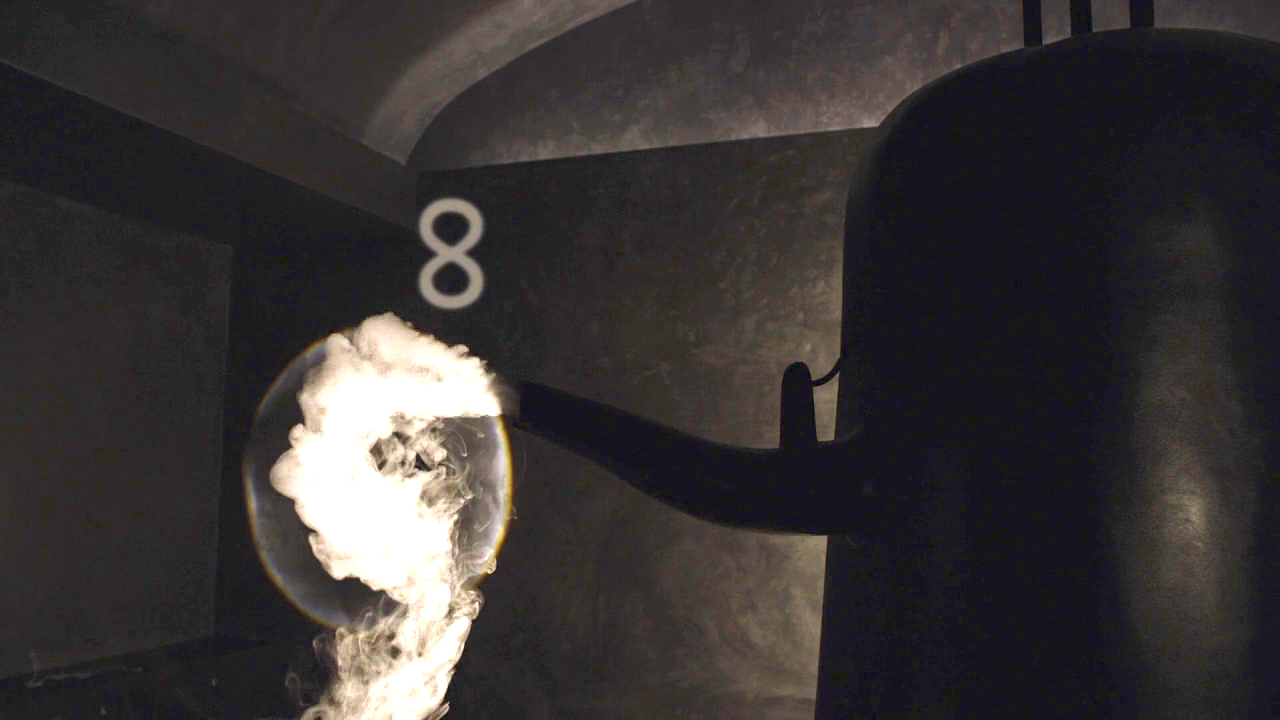

Interestingly, the Linati schema (written by Joyce) lists as Time for chapter 18 of Ulysses the recumbent 8 (∞), the sign for eternity, as well as a symbol of female genitalia. The symbol drawn in smoke by Jeffries announces what is going to take place in part 18, reminiscent of the last portion of Kubrick’s 2001: a Space Odyssey:

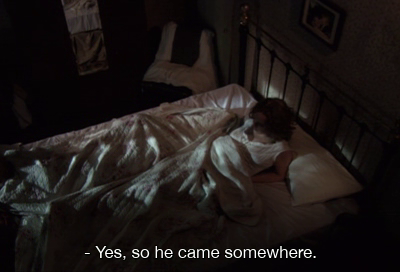

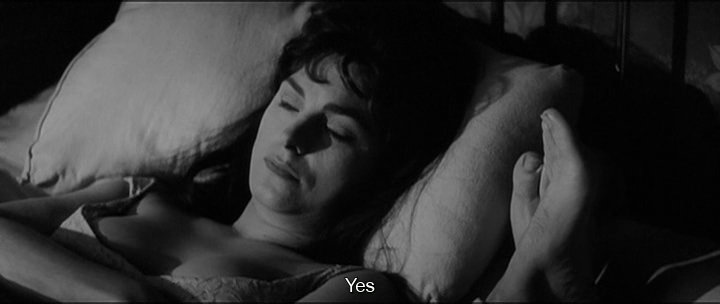

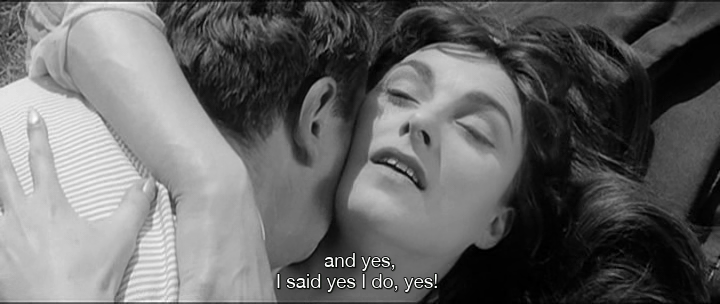

18- Penelope

The last chapter of Ulysses is famous for its long internal monologue (a female monologue balancing the male monologue from chapter 3) within Molly’s head (Bloom’s wife), in bed. It is over 40 pages long, with only 8 sentences in total. She reflects on her entire day, and the whole of her life, inside her head. It’s a real flood of words, paralleled by her menstrual flow. The keyword of the monologue is “yes”, which she repeats at central moments of her rant, most importantly at its beginning and end.

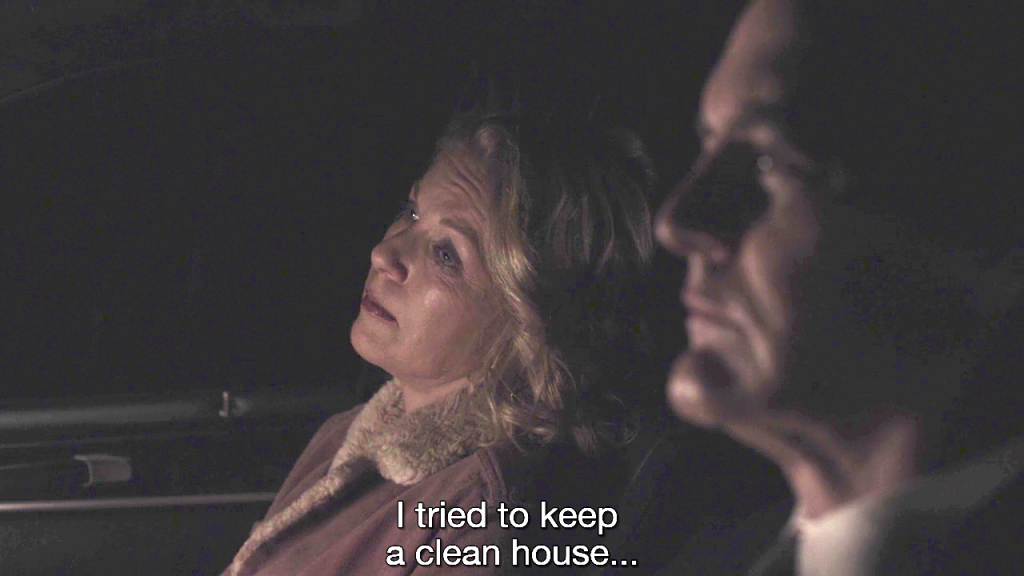

She thus becomes akin to an Earth mother, the embodiment of female fertility. Her frustrations are expressed in this chapter, especially the fact that she is denied her sexual rights by Bloom because of Rudy’s death, which leads to her distrust of other women, whom she sees as rivals. But she is also fond of remembering the day he proposed to her, the “yes” she told him then. Like him, she links Stephen to her child’s death. And she somehow sees in Bloom men at their best (the way he serves her breakfast in bed, brings her books, etc.), but she also thinks of the times when he suckled her breasts to relieve her pain — she is his wife, but also plays the role of mother and child. All of this makes an emotional homecoming for Molly. In this chapter, Molly is clearly compared to Penelope, Odysseus’ faithful wife, his true home, the place and person to whom all his journey aimed for.

As explained above, two options arise in The Return for this character: it’s either Diane, or Laura. Even though it’s with Diane that Cooper has sex in part 18, I still believe that Laura is Cooper’s true Molly/Penelope. I have several reasons for this. First, Laura is Cooper’s end destination in the season, she’s the one who comes at the very end of the journey. Then, she’s the one who discusses matters linked to her home in Odessa while they drive towards Twin Peaks, she talks about the way she did her best (as Carrie) to take care of it, in spite of all the difficulties — this monologue in the dark feels very much like the one Molly has in her Dublin bedroom. Cooper’s car becomes something of a driving bed in this sequence.

If one pays close attention, it can be noted that in the frame behind Carrie there is an exposed piece of lace. Penelope was known for weaving, day after day, a shroud for her husband’s father, which she would undo at night. This way, the shroud would never be finished, and her suitors would never get to marry her. Additionally, on Carrie’s mantelpiece, one can also see a thimble, once again linking her to textiles.

Interestingly, if Molly has a father, almost no mention is made of her mother in the book. Her father was in the British military, stationed in Gibraltar, guarding the edge of the classical world. This is reminiscent of Laura’s relationship with the Fireman, her father of sorts, also perched on-top of a rock in the middle of the ocean, guarding the universe.

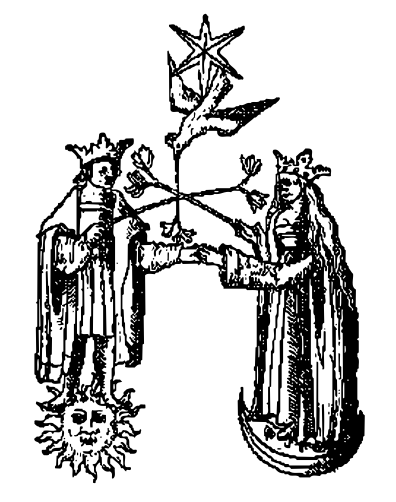

As far as a marital relationship between Cooper and Laura is concerned, it seems to me that the sequence when they both climb the stairs to the Palmer house at the very end of the episode brings to mind a couple walking down the aisle of a church to the altar. This is reminiscent of an alchemical wedding, a union of two complementary forces of the universe at last coming together — she, the “moonchild”, and he, the solar Apollo.

As I believe that Cooper and Diane summoned Carrie into existence with their sex magick ritual (they caught her in their crowleyan “butterfly net”), one could argue that Laura is akin to Cooper’s child. But she is also something of a wife to him if one thinks of their wedding of sorts at the end of part 18 and of their kiss in the Red Room in part 2. Finally, she is very much of a feeding mother to everyone (like the angel on her bedroom’s painting), in charge of the RR “meals on wheels” in Twin Peaks, taking care of everyone as Gaia is supposed to do.

She is “the One”, after all.

Child, wife, mother. Laura is the one saying “yes” to the world, despite all the horrendous things she’s seen and experienced in her short life. If Judy is pure negativity, Laura is absolute positivity.

One last thing that links Ulysses and The Return is Carrie’s shriek at the very end of the season, reminiscent of the famous Irish Banshee (mentioned in Joyce’s novel: “Strangers in my house, bad manners to them! (She keens with banshee woe)”, ch.15), this female spirit who heralds the death of a family member, usually by wailing, shrieking, or keening (a form of vocal lament for the dead).

Is this the death of her mother Sarah (Judy the Obscure) that Laura announces that way? It would seem so, when one remembers that her shriek provokes the extinction of all the electric lights in the house. Yes.

Someone once said that Ulysses cannot be read, it can only be re-read. I would argue that the same is true of Twin Peaks: The Return. No matter how good one is at gathering all the information spread over the season’s 18 parts, it’s impossible to truly understand its meaning after one single viewing session. Or after two. Or even after a dozen. The intertextuality at work here is incredibly dense, with references to a large amount of works (novels, films, records), mythological elements, esoteric quotes, historical allusions, and so on and so forth, that it takes years to get to the bottom (if possible) of such a masterpiece. James Joyce’s Ulysses might very well be what comes closest to this feeling of dealing with a complete world, connected with vast areas of global culture, interconnected to such a wide number of archetypal themes and figures.

Someone else said that if Dublin were destroyed, it could be reconstructed from the pages of this novel; Twin Peaks too could come to life if someone wanted to (re)create such a place in real life.

While Ulysses abounds with characters who have no clear motivation, who don’t achieve much by the end of the story; and is composed of a dazzling diversity of voices and styles, breaking apart the codes of the novel, a very similar statement could well be applied to Twin Peaks in general, and to season 3 in particular. This work does not try to simplify the world it depicts or its complexity. Even though one could argue that it functions according to an underlying order, hidden to the view of its audience, it certainly does not make things easy for us — and this is good. Joyce used to say that he had “put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality”. Lynch and Frost might very well have achieved something similar with their television series.

Of course, Twin Peaks quotes many other works besides Ulysses. I do not mean to reduce it to just this one novel. If we think of James Joyce, Finnegans Wake also comes to mind. Icarus’s fall is related to this novel, and Joyce’s last work is mostly about the flow of the unconscious taking place at night, when one dreams, resonating strongly with The Return. But Joyce is not the only Irishman referenced in season 3: Wilde, Yeats, Beckett, Russell… they’re all there as well. Think about the tree in Waiting for Godot, or about the face in the painting/mirror in The Portrait of Dorian Gray. Note the links between Theosophy and Crowley in relationship to Yeats and Russell. Ireland could be said to play an important role in this season.

And beyond Ireland, there’s The Wizard of Oz, Alfred Hitchcock, Marcel Duchamp, Edward Hopper, etc. Not to mention all the mythological and religious links — from the Ramayana to the Niebelungenlied, from the Bardo Thodol to The Egyptian Book of the Dead, from The Epic of Gilgamesh to The Bible.

In chapter 16, we learn that Leopold Bloom once played with a famous mathematical problem: “in 1886 when occupied with the problem of the quadrature of the circle”. Yes, Bloom himself tried his best to square the circle, i.e. to construct a square with area equal to that of a given circle using only the methods of classical geometry… and failed.

If I had presented my research as planned during the James Joyce Symposium in Dublin, I would have added more theory to this paper (much more about intertextuality, the return of the repressed, etc.). Academics LOVE theory. I don’t mind it myself, but in this case, I don’t think it’s absolutely necessary for this blog post. I hope you like it the way it is.

I have proposed various thoughts regarding the mysteries of The Return in my book The Return of Twin Peaks, in which there is a segment dedicated to Ulysses. If you’re interested in learning more, the paperback version of the book has recently been released and it’s also available in an affordable ebook copy.